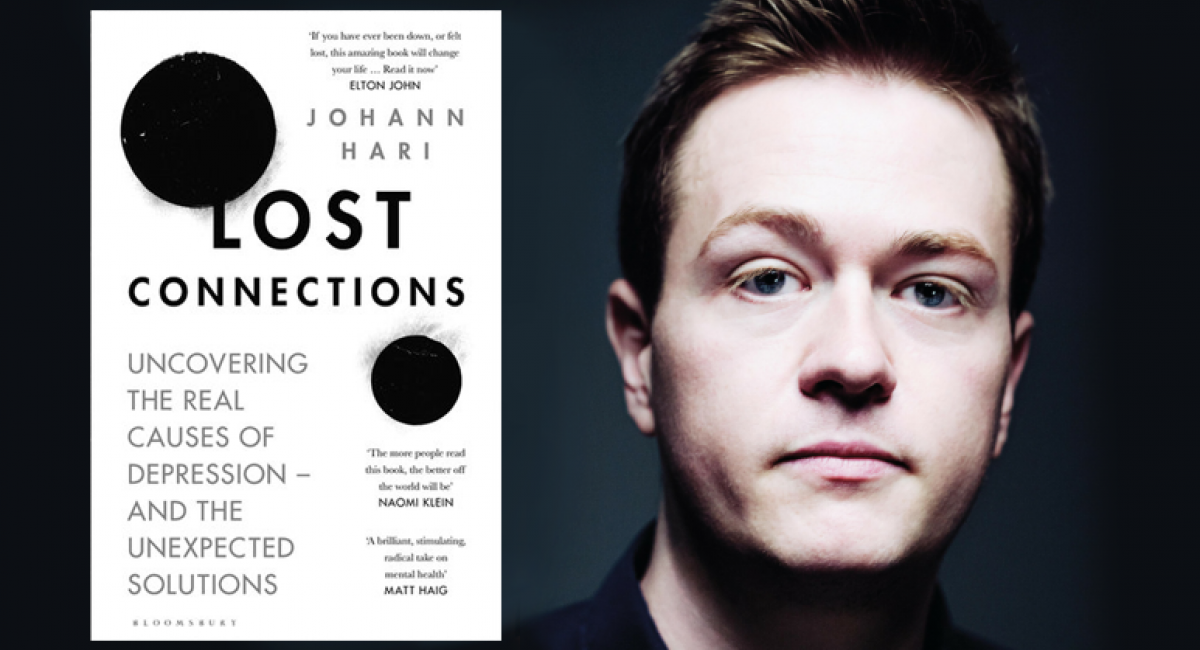

Book review: 'Lost Connections: uncovering the real causes of depression – and the unexpected solutions'

Denise Winn has read Lost Connections: uncovering the real causes of depression – and the unexpected solutions, and talked to its author, Johann Hari.

‘We all know that every human being has basic physical needs: for food, for water, for shelter, for clean air. It turns out that, in the same way, all humans have certain basic psychological needs. We need to feel we belong. We need to feel valued. We need to feel we’re good at something. We need to feel we have a secure future.’

It was these words, from Johann Hari’s new book, an extract from which appeared two weeks ago in the Observer, that caused a number of HG nostrils to start twitching. Practitioners got talking online; a number even contacted me: ‘This is pure human givens!’ they protested. ‘How come there is no mention of Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell, the founders of the approach?’ Those nostrils smelled a rat.

In fact, there was no rat (or only Rat Park, which I will come to). Having read his fluently written and insightful book, I am quite clear that Hari arrives at his understandings via his own route, one that originated in personal pain. It led to a long trawl through research and to his travelling all over the world to speak with researchers and inspirational people, doing remarkable things. His book takes a gripping storytelling approach, as if he is sleuthing his way through a mystery – as, indeed, he feels he is.

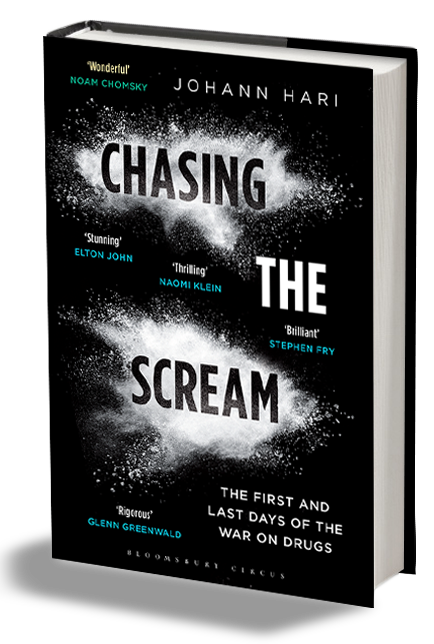

As he told me when we spoke, he first conceived disconnection as significant in mental ill health when he started to try to understand addiction, which had seriously affected people close to him. Pretty soon, he discovered the work of eminent Canadian psychologist Bruce Alexander, showing that rats in a stimulating environment will choose plain water over morphine-laced water, only resorting to the latter when kept alone in conditions of deprivation (this is also fully described in our own book, Freedom from Addiction). Then he discovered that a decision taken in Portugal in 2000 to decriminalise drugs while simultaneously instituting a major programme in social reconnection, including job creation (at a time when one per cent of the population was addicted to heroin), led to a 50 per cent drop in injected drug use.

These and other findings appeared in his first book, Chasing the Scream, and led to a TED talk. ‘I said at the end of it, “the opposite of addiction is not sobriety; the opposite of addiction is connection”. This caused a lot of curiosity. People kept saying to me, “What exactly do you mean by that?” And so I decided to research it.” His findings are in Lost Connections.

He had not at the time made the link between the importance of connection and mental health generally. Having experienced several bouts of depression by the age of 18, he visited his GP and was relieved to be told that what he was experiencing was the result of a chemical imbalance in the brain. Gratefully grasping at the Prozac prescribed him, he took it for 13 years; it only gradually dawned on him that he continued to have deep depressions, along with the other major unwanted effects, such as weight gain and loss of sexual pleasure. As he started to look into the literature, the chemical imbalance explanation revealed itself to be a myth and disconnectedness started to seem key. He describes in fascinating, highly readable, detail interviews with many eminent, pioneering researchers whose work has shown how depression rates rise when there is disconnection from meaningful work, from other people, from meaningful values, from childhood trauma, from status and respect, from the natural world and from a hopeful or secure future.

Of course, this accords, in many ways, with human givens understandings about essential emotional needs. There is a painful section in the book where Hari talks about a period of extreme violence he experienced as a child from an adult in his life. He didn’t feel able to tell his parents and he coped with it by blaming himself for the abuse. It was a way of taking back some control and serves as a stark illustration of the sheer power of the drive to meet essential needs in any way possible. As he said, when I mentioned this, ‘Yes, I could either accept powerlessness and constant vulnerability or I could believe it was my fault, and so regain some perverse form of agency in my own mind.’ But the cost was high – ‘a person who thinks they deserved to be injured as a child isn’t going to think they deserve much as an adult, either’.

The last part of Hari’s book vividly describes different types of attempts that have been made to overcome disconnection. He looks at a variety of events or activities that, in effect, give people the power to change their lives into more meaningful ones; thus the positive impact of a particular piece of community action, which drew disparate, isolated members of a deprived area together; an experience of cooperative working; the possibilities of universal income, the rediscovery of spiritual values, etc. He offers them tentatively, ‘conscious … that they might seem too small and that at the same time they might seem impossibly large’, adding that the research on impact at the moment is limited. However, from a human givens perspective, they all eminently make sense.

One of the shortest sections in this part of the book is on the role of psychotherapy in overcoming childhood trauma. If anything shows that Hari was not familiar with the human givens approach, it is this section. He offers research showing that talking for the first time about childhood trauma and being heard compassionately was found to reduce help seeking for any medical conditions in those who had suffered them. He himself has had therapy for 14 years. However, as we know, there is a much more effective, swift, non-invasive human givens treatment for trauma, which can quickly empower people to take their lives back and move on.

Perhaps the most shocking takeaway from this book for me was the reminder that so much of the research showing the biopsychosocial nature of depression was carried out in the 1960s and 1970s.

For this knowledge to have been in the public domain and ignored/suppressed for so long is nothing short of scandalous. So Hari is definitely on a quest to spread the knowledge he has discovered. His next project is to research exactly how change can be helped to happen – and, as our conversation convinced him that our thinking is much in accord, he has asked to meet to discuss what the human givens approach has to offer. I was very happy to agree as, of course, we have lots!

Lost Connections: uncovering the real causes of depression – and the unexpected solutions.

Published: 11 January 2018 (Bloomsbury, £16.99)

She is editor of the of the Human Givens Journal and for over 25 years she was a regular contributor at different times for the Sunday Times, Observer, Guardian, Independent, Daily Mirror and Daily Mail. For 12 years she was also Cosmopolitan’s medical writer as well as a contributor to a variety of other national magazines. She is former editor of a magazine produced by Mind, the mental health charity, and the UK edition of Psychology Today.

Author in her own right of 18 books on medical and psychological topics, for the lay reader, she co-authored the HG Approach Series of best-selling self-help titles on depression, addiction, anxiety, anger and liberation from pain, and Managing the Monkey with Mark Dawes.

Review posted 23.1.18

Latest Tweets:

Tweets by humangivensLatest News:

HG practitioner participates in global congress

HG practitioner Felicity Jaffrey, who lives and works in Egypt, received the extraordinary honour of being invited to speak at Egypt’s hugely prestigious Global Congress on Population, Health and Human Development (PHDC24) in Cairo in October.

SCoPEd - latest update

The six SCoPEd partners have published their latest update on the important work currently underway with regards to the SCoPEd framework implementation, governance and impact assessment.

Date posted: 14/02/2024