Pulling out positives from pain

Beth Hamilton describes the innovative workshop programme she has devised to help people cope with chronic pain.

When I was first asked to write an article about the group I run for people with chronic pain, I had a momentary panic. After all, what was I doing that the NHS wasn’t doing already? And then I realised that what I am offering is just so completely different.

Pain clinics in the NHS do really great work but there’s a high dropout rate and it is rare for a person to be able to discuss their emotional state – if they should need help in this area they are referred to a psychologist. The course I have developed is a mind/body course, all wrapped up in the comfort of a human givens blanket. I have recently completed a pilot study of it with users of Mind in Bradford.

We started out with 12 attendees – all women (not surprising, as women are generally more motivated to do something to alleviate their symptoms, whereas men tend to force on through), who had suffered severe pain for up to 20 years. Four dropped out early on but everyone else stayed the course. Most were aged between 40 and 45, the youngest being 35 and the eldest 60. We had quite a range of pain problems: severe osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis; spinal cord damage which several surgical procedures had not alleviated; lower back pain; severe headaches; and extremely painful stomach problems – a mixed bag of pain resulting from damage to muscles, ligaments, tendons, bones, blood vessels or nerves. Some group members had two or three conditions, often accompanied by anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, etc.

My programme consisted of 12 weekly workshops, each one lasting for two and a half hours. Mind had arranged for us to meet in a comfortable community centre and everyone agreed that they preferred this venue to a medical setting (they’d had enough of those), feeling more at ease with the informal atmosphere of the centre. The kitchen, where we could make coffee or tea during breaks, was especially popular as people in pain need to get up and move around every half hour or so.

In the interests of evaluation, I asked the women to complete a few questionnaires at the beginning and end of the course: one covered the history of their pain and current management, including medication; another was an adaptation of a pain inventory which includes rating daily functioning, sleep, relationships, mood, etc; the third was an outcome rating scale. To the question, “Has there been any trauma in your life?”, 10 out of our original 12 answered yes. Eleven answered yes to “Do you suffer frequent bouts of stress or distress?” As the group bonded well and were soon able to talk freely about their problems, it quickly became apparent that three women had experienced sexual abuse in childhood; two had struggled to deal with bereavements; two had been in serious road traffic accidents and another had a daughter with severe mental health problems. What follows is my programme plan, and how the Mind group responded.

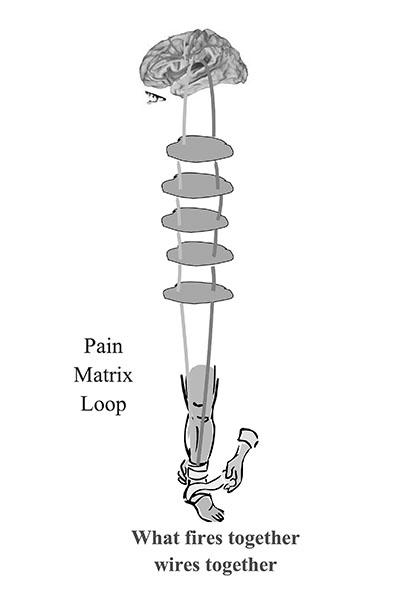

Workshop 1: The communication loop in pain

In the first session, aided by clever PowerPoint slides, I talked about the physiology of pain, explaining Patrick Wall and Robert Melzac’s pain gate theory. Put simply, when we hurt ourselves, messages are sent to the brain (via neurons transmitting chemicals in the spinal cord) to tell it there is a problem. The brain analyses the information and sends a message back down the spinal cord, releasing the appropriate healing chemicals and endorphins, etc, to where they are needed. There are pain gates in the spinal cord that allow this transmission; the gates stay open until healing has occurred, then close and things go back to normal.

However, in chronic or excessive pain, many more parts of the brain are involved, including the frontal lobe (which carries out our cognitive evaluations, based on memories of our past experiences of pain, our attitude to pain, our expectations of this latest event, the attention and meaning we give it, and what we are going to do about it) and the emotional brain, which is heavily involved with fear and anxiety. I have a nice slide of brain scans of a person experiencing acute pain and a person experiencing chronic pain. The latter is lit up like a Christmas tree.

According to the pain gate theory, in chronic pain it is the messages coming down from the brain that keep the gates open and, if the gates stay open too long, then the neurons involved become neuroplastic – ie stronger and faster at carrying their pain message, even though the pain may have lessened or even ceased in some cases. I say it is a bit like people walking across the grass in a park; if enough people go the same way every day, the pathway they make gets wider and deeper. These neuronal pathways become the brain’s default setting; when it pattern matches to other hurts and pains, physical or emotional, these activate the same pain programme.

neuroplastic – ie stronger and faster at carrying their pain message, even though the pain may have lessened or even ceased in some cases. I say it is a bit like people walking across the grass in a park; if enough people go the same way every day, the pathway they make gets wider and deeper. These neuronal pathways become the brain’s default setting; when it pattern matches to other hurts and pains, physical or emotional, these activate the same pain programme.

I was careful to explain that anatomical changes do occur in the brain and spinal cord with chronic pain (it is not all in the mind) but, with the right therapy (self-hypnosis), the changes can be reversed. The aim is to give hope immediately. Also, even if there is still a certain amount of pain to deal with, reversing the neuroplasticity in the communication loop reduces many of the associated problems.

I ended the first session with a deep, guided relaxation, sprinkled with suggestions of new learning and healing, and provided everyone with a CD of it (alas, amateur quality only), so that they could begin to learn deep relaxation for themselves before our next meeting (thus reversing neuroplasticity).

Workshop 2: Self-hypnosis

I introduce this term quite deliberately, rather than relaxation, as people have different ideas about what relaxation means – from sitting with a pina colada by a pool to slumping in front of the TV to taking country walks – whereas self-hypnosis implies getting down to business, engaging in a specific task to bring about change. I introduced the session by asking the group if they had enjoyed the relaxation the previous week. Having got an enthusiastic yes, I explained that what they had experienced was self-hypnosis (setting up a positive expectation about it) and stressed that it was medical self-hypnosis, like the kind that can be used instead of anaesthetics during an operation or childbirth.

We brainstormed myths and concerns anyone might have about hypnosis. To illustrate how hypnosis is a focusing of attention to produce change, I asked everyone to close their eyes, then placed an imaginary lemon sherbet sweet in each person’s hand and invited them to put the sweet in their mouth and suck on it. Most reported that their mouths watered, enabling me to suggest that, if imagination were powerful enough to produce saliva, surely we had the power to change other bodily functions.

I then asked them to close their eyes and think of the first time they fell in love. Did they remember how wonderful that feeling was, how physically strong and energetic they felt, how creative and intelligent, and how, during this time, they felt so well? Yes, they did! By this time, they were highly receptive to my explanation of how the placebo effect works, and the session ended with an exploration of where each of us carries stress in our bodies and a hypnotic induction involving a magic sponge for mopping up stress.

Workshop 3: Inductions

At this session, we went through a few different types of self-hypnosis inductions, starting with a mindfulness breathing exercise and moving on to an adaptation of hypnotist Jordan Zarren’s marbles induction. I gave everyone a marble and it was lovely to see each woman smile as they pattern matched back to their childhood memories. They went through a relaxation while looking at the marble, imprinting the idea that the marble meant relaxation – of course, anything else could be used instead. I also showed the arm-drop method for self-hypnosis, in which an arm is raised and not lowered until the person is relaxed enough to let it flop onto her tummy. If repeated sufficiently, an arm resting lightly on the stomach itself becomes strongly associated with relaxation, without even the need to raise it. Finally, we did “magnetic hands”: taking people into relaxation, then asking them to imagine wonderful healing energy between the tips of the fingers of their almost touching hands, lightly focusing on the sensation – perhaps cool, perhaps warm, perhaps tingly; then, when they sensed the energy was strong enough, placing their hands on a part of the body that needed soothing.

Several said afterwards that they had felt the healing energy pass from their hands into their bodies. These were women who had been anxious and in pain for years, and yet already they were experiencing their own comfort healing, which they had engineered themselves. What an astronomical leap in self-empowerment.

Workshop 4: Creating positive ‘self-suggestion’

I never use the term affirmations. It feels too woolly, whereas positive self-suggestion feels personally relevant. One woman told us she had bought a lovely pair of high-heeled shoes to go to a party but found they made her back hurt too much. Her negative reaction was, “Oh no! I’m going to have to wear flats for the rest of my life. Then I’ll have to start using a stick and I’ll be in a wheelchair in no time at all!” This was a marvellous example of racing negative thoughts and I asked her how she had felt when she thought that. “Awful. And I felt myself beginning to stoop over!” she said. I was thus able to demonstrate that what she was doing was actually negative self-hypnosis. We then set to work to identify each person’s own negative self-talk and find a positive way to express it. A useful way to do this is through people’s individual pain descriptions. Instead of thinking, “This throbbing pain will go on all night,” a positive self-suggestion might be, “When I practise my self-hypnosis, I can change the pain signals into a soothing, smooth calmness, which will allow my mind and body to rest well tonight”. Or “I have learned some strong coping skills and can use them to neutralise the discomfort and enable a good night’s sleep”. Or, when they notice a negative thought, “Thoughts are only ideas; I can challenge all negative, stress-producing thoughts because I am in control”. The aim is to get people to see that, whether their thoughts are negative or positive, they are creating a neural programme which, when repeated enough times, becomes the default setting for the brain.

I felt, however, that I hadn’t fully got the importance of this message across and was casting about for how to do so when, during the week, I saw Kathleen, a private client. She had chronic fatigue syndrome, food intolerances, various allergies and physical pain, and was now self-harming. We tracked all this suffering back to a traumatic accident but, even after successfully carrying out the rewind de-traumatisation technique, she was still left with her learned negative self-hypnosis. She was shocked when I told her that she was abusing her body as much with her thoughts as with her razor blade: “If you keep telling yourself, ‘I feel so cut up’; ‘I’m exhausted’; ‘I’ve no energy’; ‘I can’t cope with anything’; ‘everything gets me down’, that’s exactly what you are making happen. What you tell yourself is what you get.” And then I remembered ‘organ talk’ (see below). After I explained this concept, the light bulb came on for Kathleen. She no longer self-harms and is working on her physical problems.

Workshop 5: Organ talk

In the next session, after re-affirming what I had said about self-suggestions the week before, I told Kathleen’s story to demonstrate organ talk – how the negative physical descriptions we most commonly use (“life is a pain in the neck”; “I’m sick of this”) can translate into reality. I reiterated that the brain is a pattern-matching organ and that what we focus on is what we get. This resonated very readily with the group. One woman, who suffered severely with painful diverticulitis, a digestive disease which causes nausea, realised that she constantly told herself, “I’m sick of it” and “it turns my stomach”. Another, who had low back pain, kept thinking of her husband as “a pain in the arse” because he didn’t help enough. As they carried on exploring their own unhelpful language, I told them that Kathleen’s first thoughts in the morning had been, “Oh no! I feel absolutely exhausted”, but she had now decided to start saying, “My shower will invigorate and energise me”. The woman with diverticulitis, who often avoided eating because of the expected pain and so was depleting her energy even further, immediately decided to start saying, “When I eat breakfast, I give myself more power”. And the woman who kept thinking of her husband as a pain in the arse decided to remind herself that he really was doing the best he could in the circumstances.

Workshop 6: Positive imagery

This session is devoted to using metaphor and visualisation to encapsulate individuals’ experience of their pain and then change that picture to allow the pain gates to close intermittently. (I never say we will get rid of all pain, as that would lead to false hope and failure.) One woman with arthritis described her pain as like ping pong balls of all different colours being fired at the top half of her body. After throwing around some ideas, she decided to summon an army of tiny soldiers to net all the ping pong balls and take them down through her legs and out through her feet. While watching this happen, she repeated, “Cancel out pain”, then visualised a second battalion of tiny soldiers lubricating her affected joints with a giant oil can. She saw the lubrication as a thick blue jelly that was calm and cooling to her joints and said, “Job well done”. The women were interested to discover that, once they had settled on their visualisations, they could re-run them thereafter in a fraction of a second.

Workshop 7: Sleep

Loss of sleep is a big issue for people with chronic pain, leading to irritability, relationship problems and much more. So I explained in simple terms the four phases of normal sleep and that we move in and out of these phases of sleep throughout the night, depending on what we need. Pointing out that it is quite natural to return briefly to consciousness at different points during the night really helped several women, who dreaded waking up at night, assuming it was abnormal, and then began to catastrophise that they’d never get back to sleep. We started to reframe this as, “I can snuggle down and use my positive imagery for comfort and return to a deep and restful night’s sleep.”

We also took time to discuss other beliefs about sleep and what kept people awake or woke them up. One woman said her husband’s snoring woke her up, making her irritable, so we reframed this as “Isn’t it comforting that I can hear my husband lying beside me, rather than him not being here for some reason.”

I had made two audio recordings, which I gave everyone to take away – one designed to help them get off to sleep and the other to help them get back, if they woke up in the middle of the night. In the first, I suggest they have won the lottery and can build their dream house. I invite them to imagine what it would look like – a castle, a country cottage, a big house on a mountain overlooking the sea – and then to concentrate on every detail as I slowly walk them through the visualisation. I invite them to pay attention to the gate before they enter – is it wrought iron, solid wood, white wicker, solid gold encrusted with jewels? – and visualise pushing it open and hearing it clang shut and look up at the house itself. What is the roof like? What shape are the windows? What about the front door? What do they see in the garden as they walk up the path? What do they see when finally they reach the front door, open it and walk in? The possibilities are endless, as they are invited to pay attention to floors and walls and ceilings, and the decoration, furnishings and contents of every room. It is a visualisation that allows constant variety, as they can make changes to the house night after night.

the first, I suggest they have won the lottery and can build their dream house. I invite them to imagine what it would look like – a castle, a country cottage, a big house on a mountain overlooking the sea – and then to concentrate on every detail as I slowly walk them through the visualisation. I invite them to pay attention to the gate before they enter – is it wrought iron, solid wood, white wicker, solid gold encrusted with jewels? – and visualise pushing it open and hearing it clang shut and look up at the house itself. What is the roof like? What shape are the windows? What about the front door? What do they see in the garden as they walk up the path? What do they see when finally they reach the front door, open it and walk in? The possibilities are endless, as they are invited to pay attention to floors and walls and ceilings, and the decoration, furnishings and contents of every room. It is a visualisation that allows constant variety, as they can make changes to the house night after night.

In the second recording, I reiterate that it is natural to wake in the night and that people can just let themselves drift back towards sleep. To convey the idea that they can choose not to pay attention to distractions, such as their partner snoring, traffic noises or music from next door, I tell the story of Odysseus returning home by sea from the Trojan war with his men and how he kept them safe from the treacherous Sirens, bird-women with beautiful voices whose tantalising singing had lured many a sailor to his death on the rocks near their home. Odysseus had his sailors block their ears with beeswax so that they were completely immune to the Sirens’ call and they returned home safely with great treasures and riches.

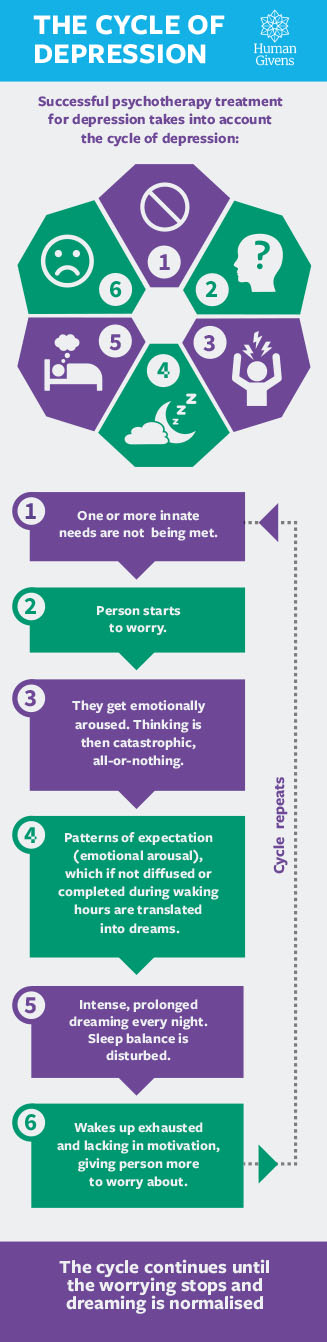

Workshop 8: Depression

As we know, sleep disruption is part of the cycle of depression. I asked each person what the word depression meant to them, the degree to which they felt they suffered it and what form it took. One woman said it was like thick oily treacle that was pulling her into its grasp, robbing her of every ounce of energy and stealing her life. (After the group finished, she and I did a little exercise together to visualise how she could get rid of the treacle. In the end, she recognised that she could pull a plug and let the treacle drain away. I asked her what was left in its place. “Oh!” she said “Diamonds and sapphires and valuable riches!”) The explanation of the cycle of depression really hit home with the group. I told them arousal caused by negative rumination has to be discharged during dreaming every night, resulting in more and more of the night spent in dream sleep and less in tissue repair sleep and, consequently, sleepers waking exhausted and lacking in motivation. Worrying about why they are exhausted or unmotivated would set the whole cycle off again.

visualise how she could get rid of the treacle. In the end, she recognised that she could pull a plug and let the treacle drain away. I asked her what was left in its place. “Oh!” she said “Diamonds and sapphires and valuable riches!”) The explanation of the cycle of depression really hit home with the group. I told them arousal caused by negative rumination has to be discharged during dreaming every night, resulting in more and more of the night spent in dream sleep and less in tissue repair sleep and, consequently, sleepers waking exhausted and lacking in motivation. Worrying about why they are exhausted or unmotivated would set the whole cycle off again.

This session closed with a guided visualisation, an audio copy of which I gave out at the end. Because people feel so low and dark and miserable and unmotivated when in the grip of depression, I counter this in the visualisation by conjuring the image of a magic carpet that lifts us up, energises and soothingly rocks us as it flies us to new, exciting places. Many people in chronic pain rarely go out and their world shuts down, becoming localised to shops at the end of the street or the doctor’s surgery. The visualisation allows their imaginations to soar and take them anywhere they want to go. I include in it the suggestion that, as they hover in the air near home again, they see a person on a street below looking joyful and moving with a zing in their step. I say, “The person looks up and you realise that it is you as you will be in a few months’ time. The person smiles at you and says, ‘Thank you for all the work you are doing right now to enable me to have this bright new future’.”

Workshop 9: Coping strategies

This is about all the other practical things besides changing self-talk and using positive imagery that people can do to help themselves. We looked, for instance, at distraction, at taking up new interests, and at positive pacing (“I allow myself to rest now, so that I can do more later” rather than “I’d better not do any more of this, in case I make myself ill”). To encourage people to start looking differently at their catastrophising speech, I got them to identify whether they tended to think of their pain as permanent, all pervasive and/or brought on by themselves. We used, as an aid, large floor cards, with sentences on them such as, “I’m always going to be in pain”; “There isn’t a moment when I don’t feel bad”; “When I’m in pain, nothing seems right in my life”; “ Every inch of me aches”; “This pain is a punishment for things I have done”; “Nothing ever works out for me”. I asked people to go and stand by the cards that they believed in for themselves and then we unpacked those beliefs; this helped them discover that pain might actually be there only a minority of the time, that it was not always at the same intensity, that people could still get pleasure, if they allowed it, and that they could use their personal responsibility to lighten rather than deepen their pain. Everyone could then work at changing the negative statements into positives of their choice.

Workshop 10: Inner conflict

This is about letting go of past hurts, distress, guilt, etc, that may be keeping the pain gates open. I explained the rewind detraumatisation technique and invited anyone who felt that this might help them to arrange a private session afterwards. (Four took me up on this. Because we had already built rapport, and I knew everyone’s stories, I found I could do each rewind in 15 minutes.) Much of the trauma involved hospital procedures people had undergone – I very often find this to be the case.) We then moved on to Zarren’s ‘scrolling blackboard’ – visualising a blackboard on which everyone could write whatever had been hurtful, harmful, frightening or emotionally unpleasant for them. Then they had to erase all they had written from the blackboard. One woman said afterwards that she felt she now had space in her head that had previously been loaded with rubbish.

Next, in a deep relaxation, people had to see themselves walking down a grand staircase, going deeper and deeper into relaxation with every step. At the bottom was a corridor leading to a conference room, and they saw themselves confidently and purposefully walking in and sitting at the head of the long table. Then they visualised seeing someone at the door who had hurt them in the past, inviting them in and trying to find out what was behind the hurt, learning the other person’s version of events and then conveying their own hurt and, if they could, offering forgiveness. One by one, everyone with whom there was unfinished business was invited in. To end the process, the participant invited into the room anyone whom they themselves might have hurt, so that they could apologise and ask for forgiveness. I followed this with a visualisation which involved each woman bringing everyone of importance in their lives on stage in a theatre, one by one, and asking whether they recognised her true magnificence – feeling validated by those who said yes, while shining a loving light on those who said no but cutting the cord of energy that linked her to that person. Everyone found this a powerful and moving exercise.

Workshop 11: Emotional needs

People in chronic pain often lose their jobs, leading to a loss of status and sense of purpose or meaning in life, as well as loss of the social networking that goes with having a job. Because they sleep poorly, they tend to be irritable and have poor family relationships, so people start avoiding them and then they lose intimacy and positive attention. They may become housebound, depressed and anxious, and maybe the only attention they receive is from GPs or at hospital appointments. So, we started this session by privately filling in the Emotional Needs Audit.

I explained what happens when emotional needs are not met, such as an increase in perceived pain levels, inability to cope, loneliness, isolation, depression etc, and told them how, after the birth of my last child, I became anorexic and depressed for two years. I was in a bad marriage with no family support and spent most of my time at home, cooking and cleaning. It was only after coming across the human givens that I realised that none of my emotional needs was being met at that time, explaining my bad experience.

Feeling that it might be too scary for the group to share their own personal experiences, we used a fictional case study through which to explore physical and emotional unmet needs and how we could help the person reclaim her life. I then invited them to look at their own emotional needs forms and spend a few moments considering how they could meet their own needs better. We ended with a healing relaxation.

Workshop 12: Moving into the future

This was the time to review all that we had covered and find out what was useful to people and what changes they had made. Everyone decided something they would like to do in the future – for instance, pursue a hobby, start applying for jobs again, go to the cinema at least once a week or invite friends for dinner. Using a floor plan, everyone walked the steps to their bright new future, in the process laying down a new pattern in the brain to which it would be easier to match later. One woman said that she had applied for a job since she began the course and had been invited for an interview the following week. So we walked along her line, rehearsing the best possible scenarios at each stage, with two invisible mentors on either side of her. Another wanted to build bridges with her daughter, so we practised visualising ways for her to do this. It was a highly positive way to end our journey together.

Did it work?

Assessment forms completed at the start and end of the programme have revealed enormously positive results. Every single person felt more in control of her pain, knew what to do to help herself and felt optimistic about her future. All had significantly reduced their pain medication, with one person stopping it completely. The woman with spinal damage reported that her consultant had noted positive changes in her MRI scan. Another had gone back to work and one was applying for work. All reported that this had been a life-changing course.

Rating scores showed that, overall, mood and enjoyment in life improved by over 40 per cent; sleep by 34 per cent; relationships by 32 per cent; ability to carry out normal tasks by 31 per cent; general activity by 28 per cent; walking by 20 per cent; and pain by 5 per cent. This is very interesting because while, as expected, there was little change in pain scores and just slight improvements in physical activity, big changes were seen in the emotional aspects of life, including a large rise in return to enjoyment. As peer support is also a vital commodity in the pain rehabilitation experience, however, this group intends to keep meeting together every month.

At this point, I am also thinking about where I am going from here. I shall run the course again and shall continue to improve, update and better evaluate it. Early next year I intend taking a proposal to local GPs who might be interested in this course for their patients. Enlightened GPs may well want something better for patients who have not benefited from statutory pain clinics. It will be wonderful to be able to show them that, when given the right information, people in chronic pain are only too ready to learn new strategies to help themselves become more autonomous in the conditions they have to live with.

Beth Hamilton spent 20 years working as an occupational therapist in numerous different specialities of the NHS, including running a chronic pain management group. She was one of the first occupational therapists to work in Saudi Arabia and spoke at the first international conference on health. She holds the Human Givens Diploma and has a part-time private psychotherapy practice near Bradford. Since retiring from the NHS three years ago, she has run a health and wellbeing programme and a chronic pain management group for Mind in Bradford.

You may also be interested in:

Human Givens College 1-day live online workshop: Effective Pain Management - help with chronic pain, learn the powerful psychological and behavioural techniques that alleviate persistent pain and accelerate healing with pain specialist Dr Grahame Brown.

View the workshop >

This article first appeared in "Human Givens Journal" Volume 20 - No. 2: 2013

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

To survive, however, it needs new readers and subscribers – if you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach – please take out a subscription or buy a back issue today.

Latest Tweets:

Tweets by humangivensLatest News:

HG practitioner participates in global congress

HG practitioner Felicity Jaffrey, who lives and works in Egypt, received the extraordinary honour of being invited to speak at Egypt’s hugely prestigious Global Congress on Population, Health and Human Development (PHDC24) in Cairo in October.

SCoPEd - latest update

The six SCoPEd partners have published their latest update on the important work currently underway with regards to the SCoPEd framework implementation, governance and impact assessment.

Date posted: 14/02/2024