How the police measure up

By introducing the human givens approach along with outcome measurements, Jayne Timmins has made her mark on Dyfed-Powys police.

I WAS thrilled when, in July 2009, I was offered a part-time job as forces counsellor for Dyfed Powys Police. I arrived anticipating the first of three days of induction into what was, for me, a completely new world, only to be told that the coordinator of the counselling service had suddenly gone on a three-month career break. Instead of gently easing into my challenging new role, I had just two hours of induction before becoming the acting coordinator of the counselling service as well as the counsellor. I could sink or I could swim; I decided to swim. Indeed, I ended up doing much more than just keep afloat. It turned out to be a massive opportunity to make a real difference.

In my three months as acting coordinator, I learned a lot about the counselling service system and became aware that there were many areas that needed revision or improvement. Dyfed Powys covers a huge area, including 350 miles of beautiful coastline, and has 50 police stations of various sizes, with over 2,000 staff in all. Fourteen external counsellors and I had to cover all corners of it. We receive about 14 referrals a month from supervisors, managers, occupational health professionals or self-referrals directly from police officers themselves. We also have to carry out annual mandatory health checks for officers deemed to be in the most high-risk roles (I’ll come back to that later). I quickly discovered that there was no evidence of how effective the service was. There were also no policies and no handbook. The external counsellors were independent service providers, contracted to work for five sessions with each client. Most of the time, however, they went well over this limit – very often taking up to 11 sessions with a client. The only time clients were in and out in as few as three sessions was when they failed to come back for their next appointments – an ominous sign.

I had long been using outcome measurement tools – usually in the form of validated questionnaires containing statements such as “I have felt able to cope when things go wrong” or questions such as “How often in the last month have you felt little interest or pleasure in things?” which clients tick, choosing from options such as “not at all” through to “most of the time”. When these are completed at every session, the forms clearly chart the client’s improvement or failure to improve and thus give valuable feedback to the therapist. I think such tools are an essential accompaniment to therapy, as they tell a story that may not otherwise be told (it is well established that therapists sometimes assume their interventions to be more helpful than they actually are1), and so I am always highly enthusiastic about them. Indeed, I was later told that it was my knowledge and use of outcome measures that had particularly impressed the panel at my interview. So, when the service coordinator decided not to return to her post after her career break was up and the job became officially mine, I suggested that we formally introduce the use of outcome measures and assess our effectiveness as a service. This went down well because, with all the expenditure cuts we were facing, it was important that we could demonstrate our value.

The new procedure

I got the go-ahead to devise a simple handbook, policies and procedures for all therapists to follow, and these were linked with new service level agreements. Counsellors had to contract to work with clients for up to five sessions – extensions expected to be the exception – and to complete outcome measurements each time. We were to use CORE 10, the 10-question form of the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE) Measure as it is quick to complete and gives a snapshot of problems/symptoms, life/social functioning, subjective wellbeing and risk. As readers of this journal will know, human givens therapists are encouraged to record outcome measurements and the Human Givens Institute is lucky enough to be a part of CORE Net, an internet-based tracking system, run by CORE Information Management Systems. Therapists enter outcomes for every one of their (anonymised) clients, allowing data to be collected from a large number of therapists working in a variety of different ways and the efficacy of therapy/therapists to be clearly demonstrated.

The new procedure with its mandatory outcome measurement did not go down well with a lot of the counsellors, who were a motley crew, mostly accredited by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy and offering between them psychodynamic, psychoanalytic, person-centred and integrative approaches, along with some transactional analysis and cognitive-behavioural therapy. The feedback I was receiving about some of their work had concerned me from the start. (I only knew that certain clients had not had a productive experience because they ended up arranging new sessions with me, as the original therapy hadn’t helped. As one police officer put it, “The counsellor was very nice but I didn’t feel any the better for it.”) As a result of the innovations, eight of the 14 counsellors didn’t renew their contracts.

Taking this as an opportunity to make good changes, I looked on professional websites for experienced local counsellors who used brief, solution-focused approaches and invited them to see clients for us. I find that police officers tend to be highly motivated people who respond well to this sort of therapy, whereas they are far less happy with the psychodynamic approach. Of course, my first port of call was the Human Givens Institute professional register but, alas, I couldn’t find any human givens therapists in my area. (Should there be any there now, I would be thrilled to hear from them, particularly if they work in Welshpool or Newtown.)

TRiM

Keeping a check on outcome measurement forms completed by clients has enabled me to see very clearly how our service is performing. Of the 14 referrals to our service a month, I tend to see seven and external counsellors see seven. The presenting problems are rarely the traumas of the job. Dyfed Powys Police runs the Trauma Risk Management (TriM) programme, which is a means for colleagues to keep an eye on the psychological wellbeing of police officers who have been involved in investigating disturbing incidents such as serious traffic accidents, assaults, murders and suicides. Suitable police officer volunteers receive special training in how to lead structured conversations to help other officers deal with the aftermath of such traumatic situations and to monitor their wellbeing over coming weeks and months. If individuals are thought to need more specific therapeutic help, they are referred to us.2

Life stresses

However, the TRiM system works so well that I receive only about four TRiM referrals a year. More usually, it is life and relationship stresses that lead police officers to seek help and, in the safe environment that I ensure I create, very often past traumas surface, such as physical or sexual abuse as a child or old car accidents, which I can then deal with using the rewind detraumatisation technique. My experience is that trauma such as child sexual abuse leaves people generally more anxious and so their threshold for coping in life is lowered. The extra stress of a job like policing can be the last straw that tips them over the top. Analysis of the CORE 10 forms up until October 2010 has shown that, although all the counsellors are about equally effective in terms of counselling outcomes, 50 per cent of the cases seen by external counsellors take between five and seven sessions, whereas I see most of my clients for just one, two or three sessions. I also appear to see the more distressed clients, according to the evidence of their initial CORE 10 scores, denoting their symptom levels. My manager was pleasantly surprised by this reduction in number of sessions – especially as it has saved her budget £1,000 in six months. However, even though the external counsellors are now working more quickly, it is still marked that using the human givens approach yields swifter results. Some of the counsellors are now expressing some interest in the methods.

Mandatory health checks

The other aspect of our counselling work that I was keen to address was the mandatory health check. This takes the form of a half-hour chat with a counsellor and by law has to be undertaken yearly with police officers in the high-risk roles of family liaison and public protection. Family liaison officers support families after the accidental death or murder of a relative. They are involved in all stages of the police investigation, from the point of death right through to the funeral, supporting the family through the coroner’s inquest and the court case, if there is one. Public protection officers are responsible for vulnerable adults and children and are involved in domestic violence and abuse cases.

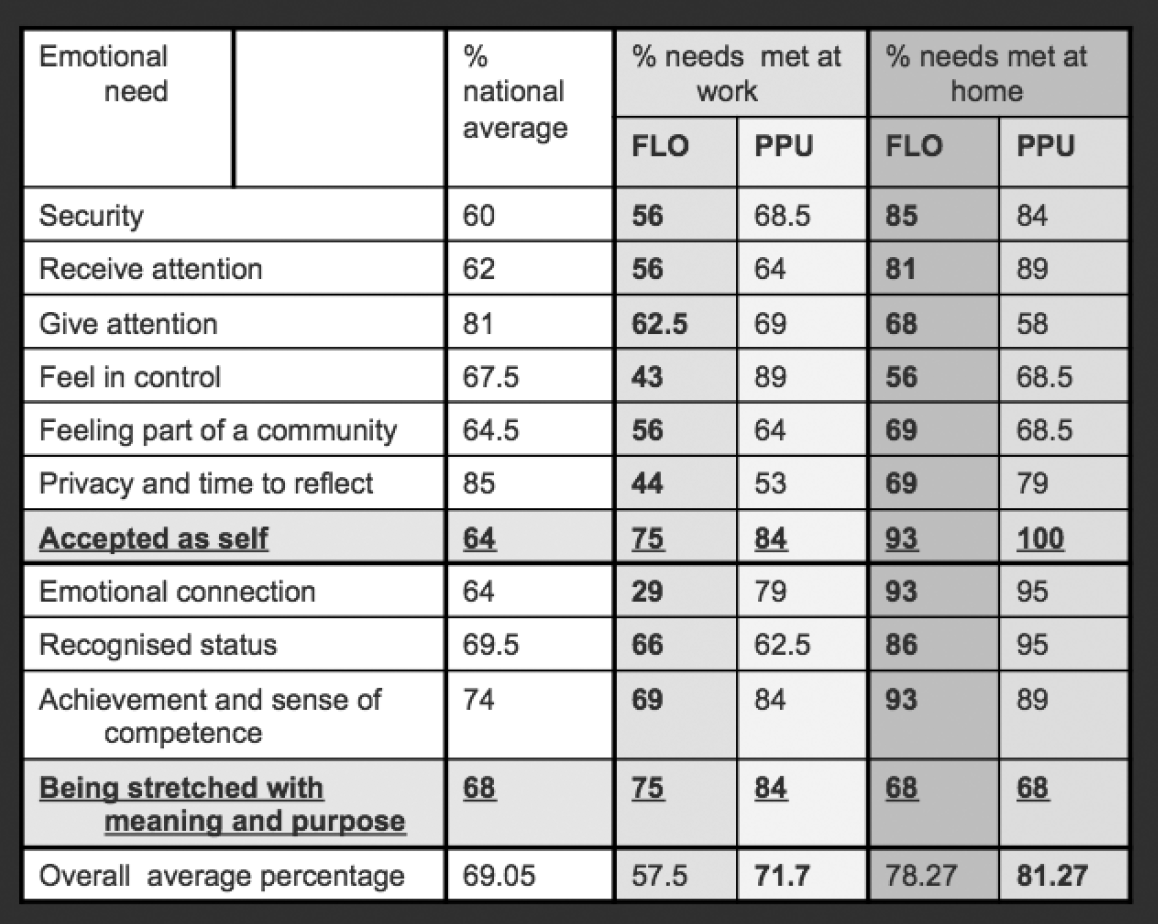

I had quickly discovered that there were no set procedures for the health checks. Often, they were as loose as a genial “So, how’s your year been?” and, not surprisingly, were felt by many officers to be a complete waste of time. I decided that we needed more structured information, so I put together a questionnaire about working roles (enjoyment of the job, stresses, work-life balance, etc) and adapted the Emotional Needs Audit (ENA) to apply specifically to home and work. I then asked all counsellors to use both, during their checks. Unfortunately, not all did so but I still ended up with data for 80 per cent of the 55 public protection officers and 50 per cent of the family liaison officers.

A puzzle solved

Although there are 52 police officers trained as family liaison officers, only 26 actually work in the role. I had already heard that family liaison officers commonly feel highly stressed, as family liaison is an add-on role and they are still required to do their normal work on the beat or in CID. But they tend to love the job, so I had wondered why it was that fully half of those who had trained specially for the role no longer wished to carry it out. The ENA immediately flagged up some answers: while family liaison officers felt great job satisfaction (81 per cent), they felt low on emotional connection at work (29 per cent, compared with an average in the national online ENA survey of 64 per cent). They also fell below the national ENA average for security – 56 per cent, compared with 60 per cent.

The police officers in the public protection unit, on the other hand, experienced high emotional connection (79 per cent), even though their job satisfaction was far lower (at 51 per cent) than that of the family liaison officers. Overall, 71 per cent of emotional needs were met in the public protection unit, compared with just 57 per cent of those working in family liaison. This started to make sense when we unpacked the story behind these statistics. The family liaison officers loved their jobs but felt unsupported in them. They felt insecure and emotionally adrift. It is those with greater empathy skills who tend to opt for the role, whereas their managers are more likely to be target-oriented ‘systemising’ types, who are less interested in relationships.3 Meanwhile, the public protection officers worked nine to five and were a close-knit team with a good internal support system. The questionnaires showed that most of the people in that unit were managing very well indeed. (In my experience, it is the beat officers who, as a result of the nature and unpredictability of their day-to-day work, are in fact much more ‘at risk’ than the public protection unit officers and may warrant a mandatory health check rather more.)

Results that led to change

I showed the results of the questionnaires to the heads of the public protection unit and the family liaison teams and both were extremely interested. On the basis of the findings, it has been decided that, from now on, it will be mandatory for the high-risk staff to complete the questionnaires but this can be done online in their own time; the results will be seen only by me and remain confidential. Only if individuals request to see someone or are found to be struggling to cope will they be invited for a face-to-face interview.

The bosses of the family liaison teams have acted on the findings in another way too. They had long suspected that their officers were not happy but now they could clearly see why, in black and white. As a result, it has been nominally accepted that officers need to work in pairs, so that they can support each other (apparently a national guideline, which had not yet been implemented). How long implementation takes remains to be seen.

My own manager is very happy about these outcomes too. Our budget has been cut drastically, yet we are still expected to do all the work that we did before. So, eliminating the mandatory health check interview except where warranted is making an enormous saving in both time and money.

Another mini-success

Little by little, more people are starting to become intrigued by the human givens approach and its quick, effective outcomes. I have lately had a mini-success in the area of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Because only cognitive-behavioural therapy and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (better known as EMDR) have the blessing of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines when it comes to counselling treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder, I am not allowed to counsel officers who have been given that diagnosis. (I do, of course, do much therapeutic work in the area of post-traumatic stress but only when it hasn’t been diagnosed as a specific disorder.) I have refused to accept this ludicrous state of affairs. Ironically, it was my prior experience of working successfully with severe trauma that, along with my outcome measurement work, clinched me my job in the first place – even though, unlike most of our external counsellors, I am not accredited with the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy.

As the cost implications are huge, I have badgered and badgered my boss to find a way to let me help people diagnosed with PTSD. I have given her a copy of the latest published data from PTSD Resolution (the project for treating post-traumatic stress in ex-service men and women), which clearly shows that the majority of severe PTSD is resolved in around four sessions when using the rewind and the human givens approach,4 instead of the usual 10–12 sessions using EMDR (as quoted by clinical psychologists). Because my manager has seen and is impressed by the results we are now getting (and has started to talk in terms of emotional needs herself), she has agreed that, when a police officer is diagnosed with PTSD, I can write to his or her GP and offer my services as an interim measure, if the officer would otherwise have quite a wait for one of the other treatments.

I am hopeful that I will be given the go-ahead by at least some local GPs and that, when they and the police force see the results, the evidence, as recorded on my trusty CORE 10, will again speak for itself.

Jayne Timmins is forces counsellor for Dyfed Powys Police. She also works as a counsellor in a GP practice, lectures for the part-time humanities degree in counselling and psychology at Swansea University and is a part-time tutor at Colleg Sirgar, Ammanford, where she teaches on the intermediate award in counselling skills and on the counselling diploma course. She is a volunteer counsellor for C4YP, a charitable organisation that counsels young people, takes referrals for psychological trauma from the charity PTSD Resolution and the Red Poppy Company and has been a supervisor for Carmarthenshire Counselling Service for the last seven years. Jayne is also a registered general nurse with 25 years’ experience; when she can, she does bank nursing shifts in Morriston Hospital, Swansea.

This article first appeared in "Human Givens Journal" Volume 18 - No. 1: 2011

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

To survive, however, it needs new readers and subscribers – if you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach – please take out a subscription or buy a back issue today.

References

- Cooper, M (2009). Essential Research Findings in Counselling and Psychotherapy: the facts are friendly. Sage Publications, London.

- For an article about the TRiM system enhanced by the human givens approach, see Prior, E (2009). Traumatic Incidents: a new way to help police cope. Human Givens, 16, 1, 20–3.

- For a full explanation of the empathising (‘female’) brain and the systemising (‘male’) brain, see Baron-Cohen, S (2003). The Essential Difference: men, women and the extreme male brain. Allen Lane, London.

- See www.ptsdresolution.org

Latest Tweets:

Tweets by humangivensLatest News:

HG practitioner participates in global congress

HG practitioner Felicity Jaffrey, who lives and works in Egypt, received the extraordinary honour of being invited to speak at Egypt’s hugely prestigious Global Congress on Population, Health and Human Development (PHDC24) in Cairo in October.

SCoPEd - latest update

The six SCoPEd partners have published their latest update on the important work currently underway with regards to the SCoPEd framework implementation, governance and impact assessment.

Date posted: 14/02/2024