No more dancing around the problem

After almost losing his life, Stuart Waters is passionate about bringing emotionally healthy practice to the dance world.

AFTER an accidental overdose of a party drug left me in a coma, followed by 35 days in intensive care, I started on the long road back to health. The physical recovery was relatively quick (I was a professional dancer and my body was used to coping with multiple challenges); it was the journey to mental health that took the time.

Halfway through that journey, I came across the human givens. I finally had a framework and the vocabulary to understand what had been happening to me, and what also happens – in perhaps less dramatic form – to so many other dancers.

The pitfalls for dancers are legion. Dance is an exhilarating practice, providing opportunities for many human givens to be well met. It offers a route to health and wellbeing, great sense of purpose and achievement, and a massive sense of being stretched. There is a gut connection to moving freely that can bring up a sense of empowerment and strength. Dancers enjoy and optionally sign up to being in a constant state of stretch, and they love being lost in sensation. The goals, macro and micro, are non-stop because the more you do, the more reveals itself that can be done. Thus there is a richness and depth to the work that remains a driver – even, in my case, 23 years on.

However, there is an extremely fine line between passion and perfectionism, as I have learned. Dancers, in my view, aren’t good at understanding the difference between stretch and stress. Re-evaluating the word passion has been highly useful for me, because I had never thought it could be something damaging, only something positive. There is an unspoken belief in the dance world that we must live up to long-accepted work ethics that, actually, are inherently unhealthy: we must be fearless with our bodies; and, if we have personal emotional concerns or worries, we must leave them at the door. In effect, we are seeking to become almost robotic creatures that can keep on going regardless. Indeed, we almost think of ourselves as superhuman beings, who can deliver whatever is asked of us. We are always open to compromising and pushing our personal boundaries in order to deliver and learn something new. And that, fuelled by the fact that we feel expendable if we don’t deliver, brings its own issues. It has been hard, for instance, to persuade dancers to accept that getting sufficient rest is vital, because, as part of dance discipline, they expect to be able to run on empty. In my experience, dancers enjoy reaching a point of physical exhaustion.

Once I had the vocabulary of human givens, I began to recognise how so many of our needs are met in unhealthy ways in the dance world. A dance company appears to be a tight community. There is the sense of being supported; your schedule is organised for you and, in a small company, you are part of a team that you work with every day. We talk about ourselves as family. After all, dancers are often doing intimate explorations through dance, which requires much trust and connection. Yet these family members are also competitors, forming, at times, an oddly ungenerous community, as we are all seeking the same opportunities to advance.

There is little privacy, with much sense that everyone knows everyone else’s business. And yet there is an irony here because, as happened for me, when things start going wrong, it is hard to disclose what is happening. Because we are so emotionally interconnected, if someone is experiencing shame or guilt or depression, the fear is that letting that be evident will have a negative impact on everyone else in the dance studio for that working day. No one wants that to happen. In trying to hide what is going on, a dancer can become quite isolated, and this may be an even bigger problem in large companies. We accept that we will experience struggle in the studio, but don’t really talk about how we will deal with it when it occurs.

The lack of privacy also means that there is no one obvious to open up to. It is impossible to feel comfortable telling the director (who is essentially a dancer’s line manager yet is primarily concerned with controlling the creative project) that you have got an eating disorder or are struggling to control alcohol or drugs; dancers are replaceable and directors are interested in those that they can rely on. Financial strains on the arts create further challenges here.

A particular issue in contemporary dance theatre is the strong slant towards deeply emotionally demanding work. Yet there is no training in dance schools for handling this delicate area. As in the acting profession, to portray a character’s trauma or depression, dancers tend to draw on their own lived experience to make it real. So they are routinely re-traumatising themselves.

So that dancers can rehearse most of the challenging physical work earlier on, while the body is fresh, it is usual for character work to be left to the end of the day. However, if a director doesn’t finish rehearsals on time, and the room is booked for another class, dancers may find themselves rushed out of the studio, still carrying all the emotion that has just come up. We may not be conscious of this, because we learn to internalise, but, as HG practitioners will know, that doesn’t mean it isn’t there. I now know that this contributed to my lack of awareness around my personal downward spiral. We cool our bodies down at the end of a class or a performance but there is no emotional cool down.

There is another kind of emotional danger that dancers and other creative artists may experience. When on tour, we have the joy of being almost constantly with an amazing group of professionals, in a deeply intimate relationship developed through, in our case, the draining and exhilarating physical and emotional demands that have been shared; there is the adrenalin of the performance, the attention, the applause, the flying to different parts of the globe. And then, suddenly, back at home, the network is gone; there is nothing to do, often no one to be with (constant travel can prevent the building of healthy social networks) and nothing more in the immediate future to strive for. The emotional crash that ensues can be overwhelming. This was certainly my experience and I know some others experience it, too.

What happened to me, ending in my nearly fatal overdose and coma, was very much the culmination of such circumstances. For 22 years, I worked extensively as a performer, teacher and choreographer, both independently and for a variety of UK and international companies. I have performed all over the world. And yet, I realise now, so much of it was a struggle. Undiagnosed with dyslexia, I had found the focus in education on literacy and numeracy crippling and, by the time I started dance training at the age of 18, I had a well-rehearsed narrative of failure, lack of confidence and low self-esteem. This was compounded by the fact that I don’t have the skeleton viewed as ideal for classical ballet, and was repeatedly told so. Thus I struggled with style and technique, while emotionally reconnecting with a familiar sense of failure. I started to use drugs and drink as a way to de-stress.

Once out in the world, I feared my lack of classical technique would stop me getting work. My feeling (as for many other dancers) was “I’m not doing enough. And I’m not doing well enough.” Dancers are hard on themselves a lot of the time because the culture of ‘don’t be satisfied’ means that, instead of celebrating what we do, we home in on what could be better. And yet, for all my fears, my experience, for 10 years, was one of no-table success. At last, I was living the dream, working for several companies with high reputations and touring the world.

As a result of that success, I became well acquainted with the emotional crashing that I described earlier. I was addicted to the highs of the whole dance world experience, not recognising at the time that I was being emotionally hijacked. After the exhilaration of performance in exotic places, Saturday back at home in my dreary rented London accommodation seemed so dull. I was exhausted and yet the last thing I wanted to do was sleep. I was experiencing what I know now to be highly intense feelings of loneliness, abandonment, restlessness, anxiety and depression, and I didn’t know how to fill my time. When I wasn’t dancing, I tried to meet my needs for connection, security, attention and achievement through other addictions: sex, drugs, food and over-exercising. I now see how being neurodiverse (having not only dyslexia but also behaviours associated with what is commonly termed ADHD) added to my difficulties in managing my emotions in a highly emotional job. Self-medicating was an easy way to calm me down.

I started to use social media and various apps to try to meet people. That is the irony of living in London – sometimes it is easier to meet people you don’t know than to set up arrangements to meet your true friends, who might not live locally. So, as a gay man, I started to go to parties and clubs where addiction to party drugs, including chemsex-related drugs, was rife. That life became an emotional crutch for me and led me into a horrible cycle of addiction. I would go mad for a week on chemsex, wouldn’t sleep or eat, and then over the next two months struggled to recover physically and sleep and eat properly again, sank into shame and guilt, vowed to change and then succumbed once more to temptation. I was gradually starting to lose work opportunities.

My overdose saved me.

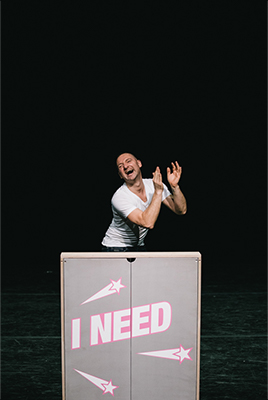

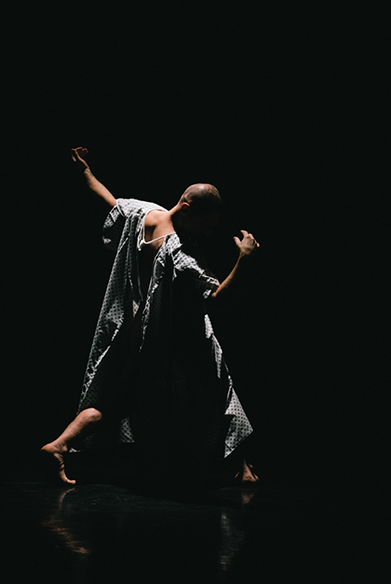

Over the months of my recovery (I was forced back to living with my parents, which was hard for all of us), I reflected every day on how I had got to this point, what I could learn about myself, and what I could do to bring good out of this terrifying experience. I found Narcotics Anonymous meetings and other support helpful to a degree but, in the end, I designed my own recovery, starting with doing something positive for my mind, body and spirit every day. Within six months I was back in dance studios and I also began to conceptualise an autobiographical dance work called Rockbottom, which would narrate my terrifying plummet to the depths of darkness and my journey back to the surface and the light. In effect, as I know now, it would show what can happen when emotional needs are unmet and innate emotional resources misused.

The project started out as a highly personal piece of work, with a very close friend (it was originally supposed to be a two-hander, although it ended up a solo show) and an extremely sensitive director. I recognised that its very production would need to embody all that I now know to be vital for emotional and physical health, so that it could be made a safe place for me to explore this difficult time in my life. I wanted to draw my audience into my world, so that they could empathise with my story but also, on reflection, see some of their own, whether or not they were gay or creative. So I needed the experience to be a safe one for them, too.

We set about trying to design safe practice, both for while we were in the studio and for the audience discussions we planned to have after performances. The first thing we did was introduce emotional warm-ups and cool-downs. We implemented the concepts of emotional check-ins at the start of day and check-outs at the end, which I still stick to. We came up with the idea of finding a single emotion word to check in with, such as “Today I might be scratchy”, which became a means to gauge the emotional temperature throughout the day. I hadn’t understood before how quickly we can slide back and forth along the emotional continuum, so this gave the director valuable in-formation. With my greater HG knowledge now, I routinely use 7:11 breathing to help performers to get into the right mental space to start a rehearsal or show and to come down safely afterwards.

I discovered human givens halfway through the development of Rockbottom when, through Suffolk Mind, I was introduced to HG practitioner Steve Peck, himself also a performing artist and founder of Mental Health and Safety, which delivers training on safe performance within a variety of settings. The cost of having him travel on tour with the team was an important inclusion in our Arts Council funding bid. It helped that mental health, autobiographical work and lived experience have become fashionable. Even so, including a psychotherapist as part of the team was a novel idea, and I feel it was a significant achievement that our bid was accepted.

We put a lot of thought into how we could run the event safely, as we went on tour with it through the UK in 2018 and 2019. We have in the UK what dancers jokingly call a one-night stand repertory culture, where typically we all get on the train in the morning, go to the venue in some city or town, set up and rehearse in the afternoon to get ready for the performance in the evening, then go straight into performing – and leave. The reason for this is partly financial. I strongly made the case to venues that, even though it would cost them more money to enable us to split this over two days, the venue had as much responsibility as we did in terms of programming the work safely, because we anticipated (and duly found to be the case) that the work, by its nature, would be highly emotionally triggering for audiences. Not all venues could comply but they did support the time for the post-show discussions.

Steve’s priority, initially, was to ensure protection was in place for me, as I would be drawing on powerful, painful emotions at every performance. I had one-to-one therapeutic coaching throughout the tour, which focused on how I could best use my own innate resources to help me meet my needs, both on and off the tour.

When we advertised the show, we pointed out that trigger-warning sheets were available, so that someone living with mental ill health or who might have a mirrored lived experience would be pre-warned about what could come up for them. We introduced ourselves before the start of the performance, and also the mental health support workers who were in the audience (we invited a representative from the local Samaritans, Mind and other mental health charities at each venue), explaining that, along with Steve, they would join a panel for an audience discussion after the show and would also be available throughout for crisis management, if required. (Sometimes, Steve had a queue after the show!) On occasion, we invited a representative from the local police, if they had a strong record of working well with mental health issues. We had also ensured that the venues would not rush us out of the building – it felt important for people to leave at a pace they felt comfortable with, after exposure to such emotionally challenging material.

The framework of human givens was used to introduce the after-show conversation with the audience – as I learned more about HG, I had realised that my show was actually a demonstration of some of its core principles. For instance, there was a section in Rockbottom called “I need”, where I was slumped over a toilet and vocalising all that I needed emotionally from my family, my friends, colleagues and so on. Homing in on unmet needs as the root of distress and addictive behaviours gave us a generic way in which people could identify with and reflect on what they had witnessed. We had no expectation that people would want to talk publicly about their own personal experiences and yet that is exactly what happened. People felt safe enough to stand up and talk about their struggles with food, or their father, or suicide, or being a gay woman, or drugs or depression, and so on.

Importantly, I got better at accessing my observing self, and being able to emerge from a highly intense performance and detach enough to be fully present at the discussion, taking a back seat but connecting with what audience members contributed. At the beginning of the tour, I had been triggering myself emotionally in order to do the show, and I was probably too triggered (for my own and others’ good), because some people in the early audiences were quite unnerved. Soon I recognised that I needed to be less emotional to do the show well, as it already had the emotional power that we wanted. The more toned-down delivery, in fact, made it safer for all of us, and allowed people to speak more honestly about their own experiences. The resource of rationality is key, I now understand. Alas, there aren’t yet enough tools in the dance sector to enable people to have access to emotion and objectivity at the same time.* The unhealthy expectation is “Dive into that emotion! Live it!”

Last year I tested the waters of change by offering an event called “Head-on”, designed as a think-tank day to bring up some awkward conversations around emotional safety in dance. Producers, directors, company representatives and funders were all invited, alongside dancers themselves. It was a rare chance to involve the people who are in control of how things work. I talked of my experience, my journey into human givens and about the needs and resources.

From that moment, I noticed that the information I shared about the amygdala and emotional hijacking was the main door opener for people to start thinking differently. It had never crossed my mind that I could be emotionally hijacked at work. The understandings break down that old-fashioned ‘leave it at the door’ scenario, once it is recognised that emotional hijacking can happen at any time. For instance, some dancers might be fine when they are practising in their own space in the studio, but then, when they have to travel across the room in front of everyone, they suddenly fall apart. Crossing that space might have a whole other pattern match to it.

HG is a great leveller, providing a safe way to have a conversation which might otherwise be quite awkward. Through the nominalisations of security, control, status, privacy etc, people can have their own light bulb moments, recognising how those are and aren’t met for them or how they may have unwittingly prevented someone else from getting those needs met. Everyone understands that what we are trying to do is to empower the room, not cast blame, so that needs can be better met for everyone in such situations. Challenging existing practices in this indirect way helps with identifying personal danger points and re-evaluating what constitutes healthy leadership in a studio.

During lockdown, I used the time to start delivering emotional safety training for artists on-line, sharing my story and journey into human givens through Rockbottom, offering ‘light touch’ HG interventional tools practical for the studio. There is, for instance, a big issue around consent in the studio. A dancer needs to be able to say, “If I am the vessel, then I should have a lot more say in this, and I don’t feel able do that rape scene today, or that suicide scene today. There are other things we can work on.”

Now the conversation needs to move on to investing money in emotional safety. The model of having a trained psychotherapist as a member of the collaborative team is, I hope, starting to catch on. Clearly, we need to be open to looking for ways to have psychotherapists in the room, so that dancers who are struggling can avail themselves of that safety net in privacy, without having to go through the artistic director.

I recently wrote what I call “The 20-year step change”, an admittedly ambitious programme containing my ideas for wellbeing training and other events, to show institutions how we can train dancers more safely. Besides conversations about wellbeing, we also need more assistance for dancers living with mental illness. Access needs are taken into account for dancers with physical disabilities, visual impairments and deafness but not for mental health needs, which might include time out to see a therapist or have in-studio support.

All these initiatives aim to put the human being at the heart of dance. HG points to the human-ness in us all and how we can benefit, in all settings, from taking that into account.

This article first appeared in "Human Givens Journal" Volume 27 - No. 2: 2020

Help us to help you – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

Help us to help you – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

To survive, however, it needs new readers and subscribers – if you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach – please take out a subscription or buy a back issue today.

* The risks from over-emotional involvement were also recognised by writer and director Stephan Perdekamp, who set up the Perdekamp Emotional Method (PEM) as a tool for actors to access emotions in a safe way, without having to draw on their own emotional memories. An interview with him called ‘Innate patterns of emotion” featured in Human Givens, vol 23, no 1, pp 28–32. Photo credits to Rosie Powell Freelance and Joe Armitage

Latest Tweets:

Tweets by humangivensLatest News:

HG practitioner participates in global congress

HG practitioner Felicity Jaffrey, who lives and works in Egypt, received the extraordinary honour of being invited to speak at Egypt’s hugely prestigious Global Congress on Population, Health and Human Development (PHDC24) in Cairo in October.

SCoPEd - latest update

The six SCoPEd partners have published their latest update on the important work currently underway with regards to the SCoPEd framework implementation, governance and impact assessment.

Date posted: 14/02/2024