Tipping the scales: an HG approach to weight management

Fiona Sheldon describes the impact of her human givens work in an NHS clinic for patients struggling with obesity.

Obesity, and the knock-on effects on health and NHS resources, is a huge challenge. A pot of money is earmarked for weight management services, ranging from subsidised gym membership and access to a personal trainer, prescribed 12-weeks access to Slimming World and Weight Watchers, through to bariatric surgery. Communicating up-to date evidence-based knowledge about nutrition and physical exercise is one challenge, but it seems to me that little attention is paid to the connection between eating behaviours and emotional health – and how we can address it effectively.

So I was delighted, two and a half years ago, to be given the opportunity to do this. A GP who knew me and was instrumental in setting up the Wiltshire county weight management clinic, known as Target, invited me to join it as a human givens psychotherapist. While there were other members of the team with cognitive behavioural therapy skills, a need had been recognised for someone to provide holistic biopsychosocial therapy for the most challenging cases. So, alongside helping patients, it has been a great opportunity to promote the human givens approach countywide and, as I had also been an occupational therapist for 35 years, I was used to working as part of a multidisciplinary team, within the constraints of the medical model in the NHS.

Target has a team of seven – two GPs, a physiotherapist, clinical nutritionist, human givens psychotherapist, lifestyle coach and administrator. We are based in a GP practice in Tidworth and patients may be referred to us by any GP in the county. Those eligible for help at Target have a body mass index of 25–40+, can weigh between 16 and 50 stones and will still be struggling to lose weight or maintain weight loss after trying the whole gamut of standard weight-loss methods. Our service provides two years of support and is also the gateway to bariatric surgery, for those who want it and meet the criteria for it. In my first 12 months, 71 per cent of patients achieved weight loss.

I see the patients who, with all the input of the service, are still struggling. They may describe themselves as ‘stuck’ or as ‘yo-yo dieters’ and often say in frustration, “I now know all there is to know about nutrition and lifestyle changes, but there is a bit of my brain that I just cannot control.” Some come to me after bariatric surgery, because even that has failed. For a high percentage of my patients, there is some sort of trauma in their backgrounds, often going back to childhood and including loss of a parent or lack of attachment at a young age, all forms of abuse at home or bullying at school/work. We run two clinics a week where I can see four patients in all, each for one and a half hours. My patients see no one else for psychotherapy, so there is complete consistency of approach, enabling us to monitor the success of human givens methods in this setting, with qualitative feedback. In the time I have worked at Target, I have seen 80 patients. They invariably gain a great deal of psychological insight, and a measure of control and ability to change that they haven’t believed possible. A very small percentage of them then opt for surgery.

As this provision is county-wide, funded by the clinical commissioning group, all referring GPs use the same electronic recording system and, with patient consent, have access to my Target notes, which record positive changes, interventions carried out, goals set and met. Every entry I make for every patient is headed “Human givens psychotherapy”, so GPs become used to seeing these words. They get to see the structure of how I work, the kind of psychoeducation I give, the outcome measures I use, and what these show. I am aware that they are reading my reports and directing referrals (for other issues) to me, as a result.

How it works

Patients being considered for Target must ‘sign up’ for two years, during which they commit to engage with all advised dietary changes, physical activity and psychological intervention. Naomi Freeman, the clinical nutritionist and service lead, and I usually run an initial introductory session in which we introduce concepts of change and balance, what it means to be human, and understandings about innate needs and resources. An Emotional Needs Audit is completed by each individual, so we have an initial measure of how well needs are being met and can begin to think about where the gaps are and why. I teach two sessions of 7/11 breathing to the group – encouraging relaxation (often an alien concept) and getting patients to imagine themselves as they want to be and to look back from there to see what they did to get to that point. We also ‘go back in time’ to when they were able to enjoy natural movement of some sort when young – such as football, swimming, riding a bike, running or dancing – so that they can reconnect with those feelings.

All patients are then referred for a medical assessment, followed by a session with the nutritionist, and, if it is identified that there are deep-seated emotional issues behind their inability to sustain weight loss, they will be referred for HG psychotherapy.

Revelations

I usually see my clients every four to six weeks for our 1:1 sessions, unless there is an urgent need for trauma work. We look in more depth at how needs are being met and how effectively their innate resources are being used. I explain pattern matching and how it is used for learning and survival, activating the flight-or-fight response, and ‘cortisol block’ which stops us thinking with our ‘upstairs brain’ or ‘thinking cap’, leaving us more vulnerable to emotional eating behaviours.

Understanding how the cycle of depression works and how the burden of unresolved emotional arousal on the dreaming mechanism causes the sleep imbalance which in turn produces a range of dysfunctional behaviours, leads to a real ‘light-bulb moment’ for many. It encourages them enormously to learn that this cycle can be reversed when the different causes of unresolved arousal are addressed and needs are more adequately met. Most have never thought about their behaviour from this perspective and can identify very well with being ‘locked’ in the ‘downstairs brain’, where emotions govern how we eat.

Understanding how the cycle of depression works and how the burden of unresolved emotional arousal on the dreaming mechanism causes the sleep imbalance which in turn produces a range of dysfunctional behaviours, leads to a real ‘light-bulb moment’ for many. It encourages them enormously to learn that this cycle can be reversed when the different causes of unresolved arousal are addressed and needs are more adequately met. Most have never thought about their behaviour from this perspective and can identify very well with being ‘locked’ in the ‘downstairs brain’, where emotions govern how we eat.

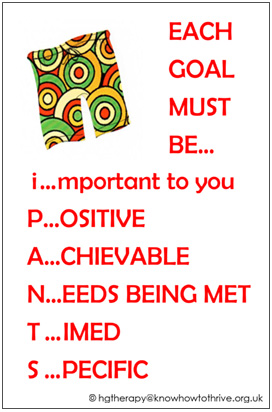

I find it helpful to do drawings and diagrams and use visual aids and acronyms (such as my iPANTS depiction of good goal setting – see image). With most of my patients, I use in8 Cards (www.in8.uk.com), which depict the needs and resources visually, aiding patients’ ability to get into their observing selves. For many, the rewind technique will be appropriate sooner rather than later because, once the trauma-associated emotional arousal is deactivated, there is more capacity to focus on positive changes to thinking and strategies to aid healthier eating. I teach almost everyone 7:11 breathing from the start, and give lots of other techniques as well to deal with unhelpful internal dialogue or ‘head chatter’. I remember one woman peering round the door when she came back for her second appointment after learning 7:11 in her first, and whispering, wide-eyed, “It’s very quiet in my head now… are other people’s heads like this?” I use story and metaphor to embed change, guided imagery for rehearsal of goals, and often provide patients with mp3 recordings, to listen to in-between times on their own.

Many patients come to me feeling powerless to change after numerous attempts, often over years. Some have lived with such high emotional arousal for so long – going back to early/preschool days when they were told that they were ‘stupid’ or ‘thick’ or wouldn’t ever be able to pass exams – that they have truly internalised that their lives can never be better. They learn that what the brain focuses on is what it gets. So it can be a revelation to learn strategies for lowering emotional arousal and getting into their ‘upstairs’ brain regularly; they realise that they do have a memory that can access resources and that they can retain new knowledge, understand, reflect, reframe things more helpfully, solve problems and make good decisions. Some get so excited that it is a joy to see!

I am very fortunate to work with an innovative primary care team that enables the time and autonomy for me to work in this way. However, we are running a grossly underfunded service for which there will be increasing demand. I currently have a one-year waiting list. So we are working on the design of supportive small group sessions to deliver the psychoeducation element of my HG interventions, which will be delegated to Naomi, already an enthusiastic advocate of the human givens approach. This will free me up to see more patients in less time. We are also considering using time spent in the Target waiting room for sharing related educational material on screen.

'Getting it'

Some of the people I see ‘get it’ immediately and transformation is swift. Oliver was a selfconfessed compulsive eater, who found it hard to stop eating once he had started. He had no sense of satiety – no natural stop button. We were both interested to piece together what had happened to him to bring about and sustain this behaviour. He had lost his father when he was very young, felt the responsibility of caring for his depressed mother and sibling and received little attention. His only real solace was food. He was overweight as an adult but managed to control his eating to a degree. Then he had married a woman who also suffered from depression and, in an evident pattern match, turned back to food.

He was fascinated when we went through the in8 Cards together, identifying the gaps in his needs fulfilment and use of his resources. As he put it himself, he began to do “an amazing amount of rethinking”. He started to feel more emotionally in control, as he increasingly understood why he had felt and behaved as he did, and what he could do to change. Armed with strategies and goals, he went away keen to put them into practice, and in his final (fifth) session announced that he had lost 26lbs in two months.

Vic, a man in his 30s who weighed 48 stone, also had an epiphany. He came from a background where there was no knowledge about the importance of lifestyle choices and good nutrition – he thought it was quite normal to knock back four litres of fizzy drink daily – and he wanted to be considered for a gastric band. For, despite, his enormous girth, he hated to feel abnormal and tried to live his life in a way that allowed him to ‘hide’. Not wishing to go to shops, he would have food and other goods delivered to his home. He had also negotiated working from home in a customer service role and was very comfortable talking on the phone, exuding a warm personality. He had plenty of Facebook friends. “I feel ‘okay’ from the neck up,” he said to me. He had great people skills. But he wasn’t able to have proper relationships, because that involved ‘the neck down’.

Once he had recognised that his needs were not being well met and that mis-information and unhelpful beliefs were getting in his way, he was able to make some highimpact changes, using his innate resources well. He dropped his litres of fizzy drink down instantly to just one can a day and started to buy healthy food online (with the goal of graduating to going into the supermarket itself) and carrying no money or cards on him when he did have to go out, so that he wasn’t tempted to buy unhealthy foods. On learning 7:11 breathing, he was sceptical (so researched it online) but now feels “positively evangelistic about it” and no longer needs his air pressure (CPAP) machine to help him breathe at night. The impact of losing two stone in two months after our first session was enormous, allowing him to stay on course and feel he was back “in the driving seat”.

He consistently met his goals (for instance, arranging and keeping medical appointments to address specific physical problems caused by his overweight and looking into, then embarking on, exercise opportunities). He felt empowered by all that he had learned and was able to recognise that strategies such as ‘hiding’ were serving only to prop up dysfunctional behaviours, with dangerous outcomes. We utilised his resourcefulness and his desire to live a normal life to maintain motivation, and he quickly developed new resources due to his newly found self-confidence. He even took on voluntary work locally, giving him the chance to connect with people (from both neck up and down) as well as some meaning and purpose. I witnessed his sheer delight as true understanding dawned and these almost miraculous changes were made.

Some people, however, rather than ‘hiding’ from their weight gain, use weight gain, consciously or not, as means to hide (for safety) – particularly the case for those who have been sexually abused when younger. Again, addressing root causes can lead on quickly to positive change.

Sometimes people’s circumstances limit what they can achieve, even when they ‘get it’. This was the case for a young woman, Joanna, who was struggling with eating after bariatric surgery and losing too much weight. Her parents were obese and, again, there had been little understanding passed down to her of the importance of healthy living and eating. Joanna had developed epilepsy in her 20s, which couldn’t be fully controlled with drugs. She was forced to be dependent on her family, because of the unpredictable nature of her fits, which put her at physical risk. She described herself as autistic and much happier without friends, finding true companionship through her pets and one supportive relative. She loved to draw and to potter in the garden.

What was most troubling for her was her lack of control over so many aspects of her life. She had no bank account, so her parents controlled her finances and she was also receiving conflicting advice from them and from health professionals about what she should be consuming and when. (Not eating was one thing she could control.) Our work helped her to find other ways to regain autonomy, and to set boundaries and assert herself – firstly, by setting up her own bank account. This increased her confidence to run her life in the way she felt best suited her. For instance, the idea of goals and plans, so useful for others, felt unhelpful for her because fits could throw everything off schedule, leading to a sense of failure. But our goal was to restore her autonomy within the limits of possibility for her, and that was definitely achieved. It felt like a huge shift, which empowered her to make healthy eating choices within the constraints of the gastric band and live as independently as possible.

Monica’s resourcefulness

It is crucial to identify and make use of whatever resources patients bring, as they so often don’t see them as resources. Monica had cerebral palsy. I could see at once that she had developed huge resilience and creative coping strategies for dealing with things that so many of us take for granted. She also had had to work harder to be accepted. She worked in an office job that she enjoyed but felt that she had to be twice as good as everyone else – and that often meant she didn’t feel able to say no to requests made of her. As a result, she got taken advantage of, as others would dump their unwanted tasks on her. Unsurprisingly, she was too exhausted after work to make proper food choices or take any exercise, and so the weight had piled on.

We worked on confidence building and assertiveness and, in guided imagery, I drew on her resilience and creativity, to embed this. A rewind of bullying in childhood and by a previous boss helped her feel much better about herself, and she was able to see that living healthily was much harder when stressed and tired, so the urgent need to restore her work-life balance became obvious and she felt empowered to negotiate realistic working hours. She was able to reorganise her priorities sufficiently to create space for herself – she loved to go swimming, for instance – and had time to see friends again. It was wonderful to see her confidence blossoming, as she built in the spare capacity to cope with a house move, too.

Not everyone recognises the emotional component in eating and that we may eat because of reasons other than hunger, such as boredom, anger, tiredness or for comfort. Jean told me in amazement, after a couple of sessions, “I never understood emotions were the reason that I was eating so much. I feel so much calmer now and I love my life again… Having someone explain why my life had become so unbearable made all the difference.” She was a school secretary who had been bullied by her manager and, as a result of our sessions, had left her job and found a much more congenial workplace.

Gastric bands

As mentioned earlier, our service is a gateway to bariatric surgery – ie people need to have engaged with us and exhausted all that we can offer before they can be referred. It is well known, however, that people can ‘eat past’ a gastric band, particularly where there are strong, often subconscious, reasons for emotional eating behaviours, and then the surgery will not deliver the hoped-for results. There are also considerable ongoing restrictions on what it is possible to eat post-surgery, which may affect compliance too. So it is a very satisfying outcome of my HG work when people who were hoping to be approved for bariatric surgery no longer want to seek it.

Another midway option is a hypno-gastric band, a specific procedure (though not currently included in NICE guidance) designed to encourage the unconscious mind to believe that a gastric band has been fitted. I am trained to deliver this, according to a set protocol, over four sessions, after treating any underlying causes of emotional eating. It involves helping people to set their goals, visualise desired outcomes and then, through guided imagery, preparing them for and talking them through the ‘operation’ exactly as if they were having it for real, complete with sounds and smells of hospital theatre, and careful adjustment of their virtual band until comfortable. Within the service I have had call to do the procedure only twice, where surgery had failed or was contraindicated.

Resilience

There have been very few people who have resisted engaging with the therapy. I genuinely treat patients as equals and have the greatest respect for those struggling with obesity caused by burdens many have carried over decades. Often their resilience through life has been extraordinary and they have achieved much in spite of everything. Borrowing from HG parlance, I often refer to myself as simply lending them my brain for a bit, while we resolve the issues causing their emotional arousal, allowing them to think straight enough to learn new ways to change their eating behaviour. Very many are extremely grateful – see, for instance, patient feedback, right. As I am the only psychotherapist they will see, they don’t have to keep telling their ‘story’ over and over – particularly welcome if it involves trauma. In such cases, I may treat straight away or I will tell them that I won’t ‘take the lid off’ anything that I cannot treat in that session – we can ‘park’ it until the time is right. That allays any fears and, for me, ensures that they are able to walk out of the clinic emotionally intact.

Spare capacity and goals

Spare capacity is key to achieving and maintaining weight loss. Marion ‘got’ the emotional needs connection with eating right from the start. She was a lively woman, who worked as a medical receptionist and, while she had always been quite heavy, her weight had ballooned in recent years. She came across as extremely interested and engaged in sessions. And then, six weeks later, I would see her again and none of her weight goals had been met. She had an adult son with mental health problems, a daughter with learning disabilities and she had experienced multiple losses for which she was still grieving. Marion had to carry the whole show and did manage to make a number of really important changes to family meals and eating habits. But each time I saw her she had a catalogue of disasters at home to report, which served to sabotage all her best efforts. Though she had all the will in the world she just didn’t have the emotional spare capacity to attend to herself at that time.

Sustained weight loss, of course, is the goal of the service. But my own goals are often very different. Marion’s aim was to fit into a particular pair of jeans. She didn’t meet that before I had to discharge her from psychotherapy, nor did she meet the weight-loss goal of the service. But she did reach my goal: I knew she went away with the tools, knowledge and strategies she needed, and the mp3s of guided imagery to help her visualise meeting her goal of getting into those jeans; and I knew that she would be able to put them to good use, when the time was right.

Sustained weight loss, of course, is the goal of the service. But my own goals are often very different. Marion’s aim was to fit into a particular pair of jeans. She didn’t meet that before I had to discharge her from psychotherapy, nor did she meet the weight-loss goal of the service. But she did reach my goal: I knew she went away with the tools, knowledge and strategies she needed, and the mp3s of guided imagery to help her visualise meeting her goal of getting into those jeans; and I knew that she would be able to put them to good use, when the time was right.

My goal is to set people free in their minds and bodies, so that they are more able to become the people they aspire to be, to set their personal boundaries, experience achievement and feel good about themselves in ways they may never have conceived – often, in the process, saving precious relationships. Whatever their weight when I discharge them, most feel that they have made significant progress. And, with the knowledge, tools and understandings they take away, we both know that they have the ongoing capacity to make changes, when circumstances allow, that will lead to healthy living and weight loss.

Fiona Sheldon worked for 35 years as an occupational therapist in a wide range of health, social care and community settings, latterly as a specialist palliative care OT for the terminally ill, their carers and families. She now has a thriving private practice as an HG psychotherapist in the Salisbury area, provides trauma therapy and resilience training for paramedics locally, and does trauma work with both ex-military and their families through PTSD Resolution. She is involved with local charity CRESS UK, providing relief and education to South Sudanese (currently refugees in Uganda), whom she visited recently to provide emotional health and trauma awareness training.

Fiona Sheldon worked for 35 years as an occupational therapist in a wide range of health, social care and community settings, latterly as a specialist palliative care OT for the terminally ill, their carers and families. She now has a thriving private practice as an HG psychotherapist in the Salisbury area, provides trauma therapy and resilience training for paramedics locally, and does trauma work with both ex-military and their families through PTSD Resolution. She is involved with local charity CRESS UK, providing relief and education to South Sudanese (currently refugees in Uganda), whom she visited recently to provide emotional health and trauma awareness training.

This article featured in the "Human Givens Journal" Volume 25 - No. 1: 2018

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

To survive, however, it needs new readers and subscribers – if you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach – please take out a subscription or buy a back issue today.

Latest Tweets:

Tweets by humangivensLatest News:

HG practitioner participates in global congress

HG practitioner Felicity Jaffrey, who lives and works in Egypt, received the extraordinary honour of being invited to speak at Egypt’s hugely prestigious Global Congress on Population, Health and Human Development (PHDC24) in Cairo in October.

SCoPEd - latest update

The six SCoPEd partners have published their latest update on the important work currently underway with regards to the SCoPEd framework implementation, governance and impact assessment.

Date posted: 14/02/2024