The carrot and the stick

Mark Evans describes how working imaginatively with rewards and punishments has helped his clients achieve very swift change.

Beer, curry and sex. Not your idea of a good night in? Well, it was for David, a warehouse manager whose anger was getting dangerously out of control, and it proved to be the turning point for him. It was the reward element of the reward and punishment strategy I have devised, which I have found highly effective in my work with a range of clients.

When David came to see me, there was little of his house that remained undamaged by his fists or feet, and his partner, to whom he was supposed to be getting married, was threatening to leave him. For some time, he had been denying that he had a problem. It was only at the continual urging of his fiancée that he finally agreed to seek help and, by the time he arrived to see me, was very upset about his lack of control.

I asked when it was that he lost his temper. He replied at once, “All the time.” “So, you lose your temper at work, with your boss?” “Ah, no, not with my boss.” “With your colleagues?” “Er, no.” Nor, he realised, did he lose his temper with family or friends, although he could get a bit edgy with them. When he thought about it more closely, he recognised that his out-of-control anger occurred only at home and only with his partner, over the minutiae of household life. This made him realise that he was already exerting a degree of control over his anger, in that he chose where he would unleash it — at home, where he felt safest and most accepted. But his partner was not accepting anymore.

I asked David what he thought would happen if he carried on in the way he was going. He admitted that he feared it was only a matter of time before he became physically violent towards his partner. He would lose the person he loved and would have nothing. “If your anger wasn’t there, would anything be missing from your life?” I asked him, and then I led him through how well his needs were being met. Nothing crucial was missing. He enjoyed his job, loved his partner and was looking forward to their life together and the plans they had made for the future. He was desperate to change his behaviour.

I taught David anger-management techniques and, in guided visualisation, had him rehearse controlling his anger when flashpoints occurred at home. Then, for some reason, the idea of reward and punishment popped into my mind. I asked him to come up with a reward for himself, if he succeeded in controlling his anger till our next session in a fortnight, and a punishment, if he didn’t. Initially we struggled to come up with either, so I asked him what he really looked forward to each week. He told me that he loved nothing more than watching TV on a Saturday night with his fiancée, while they shared a few beers and a curry. I suggested to him that his punishment could be to sacrifice this weekly pleasure, and his reward to keep it. He readily agreed. As a further incentive, I proposed that his partner also be deprived of the much enjoyed Saturday ritual, if he became angry. (I knew she would be willing to go along with that, as she had been the one initially to contact me, desperate for help.) David was more reluctant to accept this but I managed to get him to agree, as I knew that he loved his partner and that he didn’t want to deprive her of one of the now few pleasurable times they spent together, thus creating a particularly powerful incentive to deal appropriately with his anger. As yet another incentive, now that he was in the swing of it, David agreed that an angry outburst would also lead to a ban on sex for two weeks, as sex was something else that was good about the relationship.

By the end of the session David had a big smile on his face. He said, “This punishment idea really finds out who you are, doesn’t it?” I asked David what he stood to lose. He was silent for a while and then said, “Quite a lot”. For he realised that the effectiveness of the strategy lay not just in the unpleasantness of the chosen punishment, but in what the actual carrying out of the punishment represented. For him, with a house smashed to pieces and a partner about to walk out in fear of her life, the punishment he chose symbolised a devastating real-life consequence.

Two weeks later he reported back positively. He admitted that he had become angry once, but did not get aroused to the usual level. He went for a long walk to calm himself and, while out, decided that, given this dramatic improvement, he had earned his reward. I saw him a month later, and still there had been no need for the punishments to kick in. Life was so much happier and more harmonious at home that he felt less and less desire to get angry. Through our sessions he had come to realise that his inappropriate anger stemmed from childhood, when, at around the same time, his parents divorced and he himself was diagnosed with diabetes. An unvoiced reaction of “It’s not fair!” and “Why me?” had manifested itself in anger towards those closest to him, even over minor things such as whose turn it was to do the washing up or whether he had done it properly. Gradually, it became habitual. However, he found — through the rewards and punishments — that he could let it go.

Since then, I have worked quite a lot with what I describe to my clients as a reward and punishment strategy, whereby positive thinking and behaviour are rewarded and negative thinking and behaviour are punished. I tell them that this is in line with the way that the brain works — the reward makes it more likely that the positive behaviour will be repeated, further reinforcing and strengthening the associated connections in the brain, while the prospect of punishment lessens the negative behaviour, making it less ‘advantageous’ to repeat and thus weakening the connections in the brain. I find that explaining the physiology — I often talk about which bits of the brain light up when reward circuits are stimulated and so on — further helps clients ‘buy into’ the idea and commit to carrying it through.

Powerful concepts

Perhaps its success has to do with the fact that the concepts of reward and punishment are powerful ones. In my experience, the strategy helps people to focus less directly on their difficulties and more on what they stand to lose or gain by dealing positively or not dealing positively with them — another way of creating the all important reframe. Asking clients to come up with a reward and punishment usually results in their pattern matching to something they know they love or hate doing, which gives them the motivation. As Joe Griffin terms it, they now have the ‘carrot and the stick’.1 As to its long-term effectiveness, I make no bold claims but, in conjunction with all the other ‘tools’ that form part of the human givens repertoire, I have found this a useful strategy to employ.

It is interesting to observe the trouble clients often experience in thinking up a reward for themselves, a difficulty that seems to affect them less when deciding on a punishment. This makes sense to me, if it is true that negative emotional states can literally prevent us from accessing positive memories. Time and again, I have to leave clients to think of a reward, after they leave the session.

While I often use the reward/punishment strategy with private clients, I do so with less frequency than with the student clients I see, through my work as a counsellor in higher education. I suspect that this may have something to do with the client group, as almost without exception the students are enthusiastic and willing participants in developing their own particular version of the strategy. They have brought forth some ingenious rewards and punishments, conjured from their own imaginations. It is then their reward and their punishment and, on the whole, they tend to go through with it.

The household chore

Victoria was a second-year business studies student who had fallen far behind with her studies, due to depression. When I put the strategy to her, she had suggested some sort of household chore as her punishment for not getting down to work: the house she shared with fellow students was a serious health hazard. I often discuss with students some of my own university experiences as a good way to develop rapport, and it was a story of my own about the rather unhygienic bathroom facilities of my second-year accommodation that led her to choose her punishment. She immediately volunteered that she found toilet cleaning particularly unpleasant. They had a cleaning rota but never stuck to it, with the result that the toilets (they had two) were “disgusting”. To her credit she gamely agreed that, if she did not make a serious effort to get back on track with her studies, she would clean the toilets for her fellow housemates — for a month!

Sometimes, I do a little acting, playing the part of the client’s brain as if it were talking to them. With Victoria, it went something like this: “So you make me stay in bed all day, throw away my degree, stop me seeing my friends and then, as if all that weren’t bad enough, you go and kick me when I’m down by forcing me to clean toilets for a month. You’ll forgive me if I appear ungrateful.” We then worked out a study timetable that mapped out exactly what work needed to be done and by when, and I led her through guided imagery, in which she saw herself in the library completing the agreed tasks. We arranged to meet in two weeks.

At our next session a smiling Victoria announced that she hadn’t cleaned a single toilet! More importantly, she was getting out of bed at a respectable hour of the morning and heading off to do her study work.

Another household example was one of my own devising, to help a student presenting with long-term clinical depression. When I saw Jessica for the first time she was so very low that the whole room was permeated with her depression. She had been suffering this way on and off for five years and her boyfriend had just left her, unable to cope any longer with her depression and consequent self-harming. She told me that all she wanted was to be able to get up in the morning with her friends and make it to university. She had four other housemates, all of whom were keen to help, as her depression was causing them all distress. Working on the hypothesis that most students might consider it a welcome treat if a nice cup of tea was brought to them in bed each morning, I proposed as her punishment that she get up especially early and make all of her housemates tea in bed if, on the previous day, she had failed to get up to go to university. Her housemates were told that this was part of her attempt to lift her depression. I left Jessica to come up with her own reward.

To help her start to make small changes to her routine, we agreed that she would set her alarm clock and put it on the other side of the room, next to a piece of paper on which were listed all the reasons for staying up and getting on with the day, instead of going back to bed.

In our second session a week later, Jessica bounced in with a huge smile and announced that the whole mood of the house had changed, including her own. She had not got out of bed as intended on the first morning but so obliged had she felt to honour her commitment to her friends that it had been relatively easy for her to get up early the next day and make and dispense the tea. This caused much laughter with her friends. Once up, of course, it was much easier to decide to head off with them to university. She soon got into the routine of making everyone tea, even though she didn’t need to, and the result was that she felt connected to her friends again, simply through this small gesture. What had started off as a punishment soon became transformed into something much more like a reward. (Interestingly, she hadn’t managed to come up with one.)

In her third and final session, Jessica decided to write to her ex-boyfriend, just to let him know that she had turned things around for herself. She wasn’t expecting that he would return to her; she just wanted him to have a different picture of her in his head, from the miserable, insecure young woman who couldn’t understand why anyone would want to know her. (We had done a lot of work on challenging negative beliefs.) Writing down all the positives about herself for him to read made her feel good too, of course.

Hopping happy

Georgina gave me the idea for using hopping therapeutically. She came to see me at the university for help with obsessive behaviour, which manifested itself in the compulsive checking of her work (anything up to 100 times) and overwhelming anxiety when it came to actually handing it in to her tutors. She had reached the stage where so anxious did she become that she was unable to hand in any work at all. I explained the reward and punishment strategy to her in our first session, and she said that she would give it a try. We agreed that she could check her work a maximum of three times to earn her reward, but, if she checked a fourth time, she would need to suffer her chosen sanction. If she checked her work no more than the maximum times allowed but then failed to hand it in, the sanction would still apply. She couldn’t think of a punishment or reward on the spot, but undertook to do so after the session. (In my experience, clients do keep their word, once they have agreed to the strategy. That is, they always think of a punishment. Sometimes, as mentioned, they don’t come up with a reward, and it doesn’t seem to matter.)

I saw Georgina a week later and was informed that her obsessive behaviour had disappeared. She had chosen for her punishment hopping up and down on one leg 100 times and for her reward a cup of green tea. (This was a real treat because green tea is more expensive than normal tea and not normally on her shopping list.) On her first attempt, she had failed to stop at her third review of her assignment and described to me, while convulsed with laughter, how she had bounced all around her room on one leg. Apparently it really started to hurt when she reached 60 hops and making it to 100 was agony. Keen to avoid repeating her punishment, she found it easy after that to check three times and hand in the work, thus earning her cups of green tea.

“If only…”

This gave me inspiration for when I worked with a student called Sarah. Her background was different from that of most of the students she had met — she came from a family where people expressed their feelings by shouting, swearing or lashing out, and she had been involved in many abusive relationships, some of them violent. She was worried that her own tendency to get angry easily was pushing away the new set of friends she had made at university, including her boyfriend. She said that, before, it had “worked” for her to get angry but now it made her “look different”. What was evident was Sarah’s sense of humour. She smiled a lot and wryly poked fun at herself, so I felt comfortable suggesting to her that the punishment of hopping could save her relationships. I suggested that, when she felt herself becoming angry, she start to hop and keep going until she reached 100. Whether she was alone, out in public with her friends or in her bedroom with her boyfriend, she was simply to start hopping. Intrigued, she contracted to do this but couldn’t settle on a reward, despite our discussing several possibilities.

A week later, Sarah announced that the hopping had been a success. It is rare that I am reduced to hysterics in a session, but I was, on this occasion. Sarah told me that she had experienced anger only once in the week when, suffering a bout of writer’s block while trying to finish an essay, she felt herself getting worked up. As her boyfriend was with her, she knew where it would all end and so, right on cue, she started to hop out of the room. At this point her boyfriend decided to do the same. “He just looked ridiculous,” said Sarah. “He’s 6ft 7, for god’s sake!” As they were both heading along the landing like kangaroos, her boyfriend shouted, “If only you’d known five years ago that all you needed to do was to hop!” After that, Sarah reported no more problems and she brought our sessions to an end. Perhaps this was the reward in itself, because she never mentioned coming up with one.

Obsessive phone calls

I was also able to help Lisa, a friend of mine, through the use of hopping. Lisa came to see me because she was obsessively calling her partner to make sure that he had not been involved in a car crash. Her partner Robert’s journey home, which involved a short motorway journey, was 30 minutes of “torture” for her. Lisa told me that, while she had started off calling only after 5pm, to see if he was okay, the problem had escalate to the point where she was calling throughout the day and at the most inappropriate times for Robert. As I was a friend, I was familiar with their house and knew that their letterbox was, American style, situated at the end of their relatively long, gravel drive. Having introduced my reward and punishment strategy to Lisa, I wondered out loud whether the distance to and from the letterbox was too far to hop. “Well, it’s quite far,” she said, looking at me askance. “Is that my punishment?” “If you like,” I said. “But I don’t understand why you think this will work,” Lisa protested. “Trust me,” I said. We agreed that she would call me in a few days with a progress report.

Lisa called three days later and reported that, although she had hopped several times, she was still compulsively calling Robert. Uncertain whether the strategy had failed — after all, I had suggested the punishment, not Lisa, although she had agreed to it — or whether it just wasn’t deterrent enough, I ‘ordered’ Lisa to hop to the letterbox and back not just once, but twice if she called Robert inappropriately. We agreed to leave it a week before talking again. A week later, Lisa reported back. She had made no calls in three days. She now emails me weekly and, although she still finds it hard not to worry (for which I have suggested strategies), the thought of hopping is enough for her to leave the phone alone.

Enjoying the feeling

Sometimes, people come up with their own ways of working with the strategy. Priti, an art and design student, was so anxious about having to give presentations that, despite being in her final year, she was considering leaving her course. When she came to see me, she was in floods of tears, as she was a committed student and wanted nothing more than to achieve her degree. She knew that she needed to boost her confidence and, in our first session, we agreed that she would give mock presentations to her friends and family and would ask her tutors if she could give some to them as well. I did some relaxation and guided imagery with her, but she found it hard to relax fully. I then decided to introduce the reward and punishment strategy. Priti was interested but didn’t want to devise any special reward or punishment: she felt certain that the positive and negative feelings associated with making/not making positive changes would suffice for both. She knew very well how she didn’t want to feel, she said, and that was enough.

When Priti came back for her second session, little had changed. She had found that the ‘punishment’ of feeling worse had not been enough to motivate her and her anxiety had simply increased. We needed to find a specific way for her to experience her reward of feeling better. In our discussions, she had happened to mention that her parents ran an Indian restaurant. I asked her if she ever worked in the restaurant. She said that she did, but only in the kitchen or preparing drinks.

“What if you were to waitress?” I asked. “Do you think that would help build your confidence?” She said that it might, but she became visibly anxious, her eyes welling up. We agreed that she could start off slowly, by waiting as much or as little as felt comfortable on a Monday night, gradually increasing the time she spent “out there”, as she put it, as the week progressed towards the busy weekend.

By our third session, Priti was transformed, exclaiming as she sat down that she couldn’t wait for her presentations. By the Saturday night, she was waiting as confidently as her parents and sister, and felt great. Of course, her reward had changed from simply feeling better to being able to graduate. “If I don’t give my presentations,” she said, “not being able to graduate would be the worst punishment of all.”

Playing safe

In Nick’s case, it was the strength of connection to a group of people and his own sense of meaning and purpose that underpinned his chosen reward and punishment. He had come to see me for obsessive behaviour, which manifested itself in the ritualised checking of plug sockets and electrical equipment — all to make the student house ‘safe’ before he went to bed, so that no one would die that night. He found it hard to think of a reward and wasn’t at all motivated by the types of rewards most other students choose, such as going out for a beer on a week night or buying a new CD. I knew he was a helper at a scouts’ group, which he was highly committed to and so, on a hunch, I wondered whether his reward might be to give something extra to the group. “Do you mean financially?” he asked. “Not necessarily,” I replied, “but do you feel that is a possibility and you could afford it?” He said he could and seemed pleased to accept the idea.

He didn’t come up with a punishment. For him, probably, not being able to give something would have been punishment enough. Knowing that he felt it was important to be safety conscious (the reason for his obsessive checking), I wondered if his scouts would also feel good if he showed them how they could do the same? He immediately decided to devise a presentation to deliver to his scout pack on being safe in the home. He agreed to place special emphasis on having to check plugs/electrical appliances only once, as this was enough! I have yet to see Nick again to know how this has worked out, but I am hopeful.

I am not claiming that I have stumbled on anything new with my reward and punishment strategy. It is common in human givens therapy to set tasks and agree consequences that follow this pattern. However, I have been interested to see how this strategy can be effective so quickly in helping individuals change unwanted behaviours. As already discussed, it is usually the punishment element that is more salient. When a negative action is reinforced by a concrete self-imposed negative consequence, an element of distancing is immediately introduced. It is, perhaps, the equivalent of counting to 10 when angry, in that bringing the immediate consequence to mind gives time to stand back, reflect and make a rational decision, motivated by what we desire to avoid or attain. It seems to me that this helps to change the meaning or pattern that characterises thinking and behaving in a really powerful way.

It fits, I think, with veteran therapist Bill O’Hanlon’s observations at the start of his recent book Change 101 2 “If one considers human history, one can quickly discern that there are two main things that motivate human beings: things they want to avoid or get away from and things they desire or want to go toward”. Some people are more powerfully motivated by what they want to avoid and some by what they want to achieve. But the end result is that they do achieve what they want.

Mark Evans is a counsellor at De Montfort University, Leicester. He holds the Human Givens Diploma.

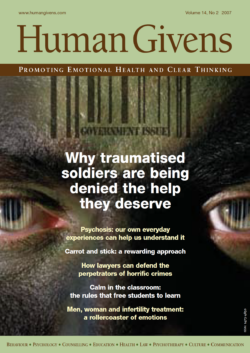

This article first appeared in “Human Givens Journal” Volume 14 – No. 2: 2007

Back issues available – each issue of the HG Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more, with no advertising. If you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach, you can buy a back issue today, they’re available in PDF and print format.

References

- Griffin, J (2004). Great expectations. Human Givens, 11, 1, 12–19.

- O’Hanlon, W (2006). Change 101: a practical guide to creating change in life or therapy. Norton, New York, London.