“But he gave me flowers”

Ros Jeal describes how she is helping women stop themselves from being lured back into abusive relationships.

IT WAS my encounter with a young woman called Becky that first gave me the idea of systematically applying the expectation theory of addiction1 in my work with women who have suffered domestic violence. I listened as she told me what had brought her to my therapy room. She had left her partner Jim a month earlier, after enduring a catalogue of horrendous emotional, physical and sexual abuse for the previous two years and becoming fearful that the anger she occasionally saw her partner direct towards her four-year-old daughter would turn into “something worse”.

She was now housed in a small flat in a different area of the county. Her daughter, she told me, was already “loads better – not so clingy” and it was a great feeling to be able to “do stuff without wondering if he was going to go off on one”. But she still felt very anxious, a bit lost and had been experiencing panic attacks. For the next couple of sessions we made good progress. Becky mastered 7/11 breathing and found, to her surprise, that it enabled her to calm herself down and deal more easily with the symptoms of panic. We used the non-invasive rewind technique for resolving her traumatic memories. And we focused on getting her needs met – building the security of her new life, planning where and how she could make and meet new friends and engage in meaningful activities – she became excited about the prospect of searching for a part-time job, once her daughter was more settled at nursery. The seeds of what appeared to be a brighter future were being sown.

But then, between the third and fourth sessions, she had a text from her ex-partner saying that he was sorry, that he loved her and that he wanted her back. He couldn’t live without her – he wasn’t sleeping or eating – and things would be different if she returned. By the time I saw her next, she was thinking of going back. “I know I’m stupid,” she said, “but he’s like a drug or something. I’ve left him loads of times before – gone to my mum’s or a friend’s, thinking I’m never going back. But I always do. I still love him. I just haven’t got the willpower to stay away.” Her use of this language made it suddenly and abundantly clear to me just how closely this cycle of leaving and returning, so familiar to anyone working in the field of domestic abuse, links into human givens’ understandings about addiction.

But then, between the third and fourth sessions, she had a text from her ex-partner saying that he was sorry, that he loved her and that he wanted her back. He couldn’t live without her – he wasn’t sleeping or eating – and things would be different if she returned. By the time I saw her next, she was thinking of going back. “I know I’m stupid,” she said, “but he’s like a drug or something. I’ve left him loads of times before – gone to my mum’s or a friend’s, thinking I’m never going back. But I always do. I still love him. I just haven’t got the willpower to stay away.” Her use of this language made it suddenly and abundantly clear to me just how closely this cycle of leaving and returning, so familiar to anyone working in the field of domestic abuse, links into human givens’ understandings about addiction.

As I work for a national charity which helps women who have experienced domestic abuse, I am often asked, “So are women addicted to abusive relationships?” My answer is, in inimitable Vicky Pollard style, “Yeah, but, no, but …” To say an unequivocal ‘yes’ seems in some way to perpetuate the myth that women choose abusive relationships, that they actively look for men who will treat them badly and then become involved with them. Plenty of uninformed people may assume that “she must like it if she stays with him” or “she always goes back to him, so she must enjoy it” because the situation doesn’t make sense to them. But, almost always, research shows that this is not the case. For 52 per cent of women who report abuse, the first incident of domestic violence occurs after more than a year in the relationship, with only six per cent reporting that they experienced abuse in the first month.2 Women no more seek out the ‘abuse’ in a relationship than a cigarette smoker seeks the carcinoenic properties of a cigarette or a drinker the liver-destroying properties of alcohol. What they are addicted to, what hijacks the reward pathways in the brain and becomes ‘the carrot’ that makes them return to or stay with abusive partners, are the elements of the relationship that are pleasurable and that meet (or masquerade as meeting) their emotional needs.1

In order to understand, then, why a woman would be tempted to return time and again to an abusive relationship, it is instructive to look at the mechanics of a ‘typical’ abusive relationship through the prism of our innate emotional needs. (I am focusing on women, as I work with them, but all my observations are equally relevant to men in abusive relationships; data from Home Office statistical bulletins and the British Crime Survey show that men made up about 40 per cent of domestic violence victims each year between 2004 and 2009, with men far less likely to report incidents than women.)

In an abusive relationship, control by the abusing partner, often exerted through violence of an emotional, sexual or physical nature, is a key feature. As the abuse escalates, the victim’s sense of volition – so important for a mentally healthy life – is destroyed. Perhaps she is no longer allowed to dress as she would like, meet with whoever she would like, call her friends on the telephone. As a result, her connections – both close emotional connections to her family members and links to her wider community – are broken. Her sense of security is shattered as she is beaten or sexually or emotionally abused in what should be the safety of her own home. She begins to question her competence as a human being, as she is continually told that she is useless and also, perhaps, because she witnesses her children suffering, yet cannot seem to leave and take them away. Any sense of status or meaning and purpose that she once derived from her role within the family is destroyed. The abusive partner scythes through her life like a drug personified, knocking out the healthy fulfilment of one after another of the basic needs that we all share.

Meaningful emotional blackmail

Perhaps most potently of all, as the abused partner becomes more isolated, any brief moments when her basic needs are met involve the abuser. The horrendous beating followed by the apology and the flowers and being told that she is ‘loved’ or that she is ‘the only one’ provide her with the only sense of emotional connection she may get. His seemingly heartfelt protestation that “I can’t live without you – I’d kill myself if you left” is blackmail, yes, but also fulfils her need for meaning and purpose – the need to be needed. These are the emotional ‘highs’ that feed into the addictive process – ‘highs’ that occur at a time of already significant emotional arousal. An abused person often experiences high levels of anxiety and frequent panic attacks, and may be hypervigilant, depressed or have post-traumatic stress disorder. And, as anyone familiar with the basics of our physiology understands, high emotional arousal shuts down access to our thinking brains, forcing us into ever more primitive black-and-white thinking. This means that these ‘highs’ take on even greater significance, becoming life rafts to cling to in a threatening sea. It seems that giving up the relationship, leaving, staying away, would mean giving up even these fleeting moments of pleasure which occur when needs are met in this way.

The sticky web

In their emotionally aroused state, abused partners have no access to the part of the brain that could problem solve, see the bigger picture and identify other ways of getting these needs met. Finally, into this maelstrom, enters the idea of love. Being ‘in love’ with someone has huge import and significance to us as a species. It transcends the niceties of behaviour and has prompted some of the best, and been used to excuse some of the worst, acts in our history. It is undoubtedly a state of high emotional arousal, which, again, makes us less intelligent and prone to acting irrationally. Because at the moments of exquisite pleasure, when the flowers are offered and the effusive apology delivered, the abusive relationship masquerades as ‘the real thing’ – and, because pattern matches fire to experiences or imaginings of what a loving relationship is really like, a particularly sticky web is woven.

This is where an understanding of the ways in which human givens practitioners work successfully with addiction can help us make sense of and find a way through the tricky circumstances of domestic abuse.

The cycle of change

Because women who are in or have recently left an abusive relationship are almost always still highly emotionally aroused when they first come to see me, they are unable to think straight, to plan effectively for the future or see their situation clearly. One of the tools that I find particularly useful, after calming them down, is the model for therapeutic change devised by James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente,3 which will be familiar to all who use the human givens approach to working with addiction. It enables clients to take a step back and access their observing selves, so as to start rationalising and putting into context what they are and have been experiencing. The cycle of change, adapted for use in this setting, is highly apposite for the patterns of behaviour found in domestic abuse; clients can engage with it cognitively and identify where they are, where they have been and where they might go, rather than simply being mired in the directionless experience of a destructive relationship. The cycle is as follows:

- Pre-contemplation: you are in love with your partner and are reluctant to admit a problem may be developing.

- Contemplation: doubts begin to creep in. Perhaps your relationship with your partner is damaging your other relationships or your work. You want to leave but at the same time don’t want to.

- Determination: at this point, something tips the balance – perhaps a clearly negative consequence of the relationship, a serious injury or a realisation of where it is leading. It is like a door opening. At this stage you either move on through the door or go back to the previous stage.

- Action: you go through the door and decide on a plan of action. You decide on a strategy, set your goals – to move out/leave the relationship.

- Maintenance: now you have to stay away.

I explain that, unless they are well prepared, many women don’t manage to stay away. The result is that they go right back to the beginning, to pre-contemplation, putting out of their mind all thoughts of how damaging the relationship is, so relieved are they not to have to struggle with their feelings any more. But many others, once properly prepared, do succeed the first time and, for the rest, the more times they go round the wheel, the more likely they are to leave successfully in the end. Each time they go around the wheel, they are learning about what does and doesn’t work for them and what they can do to get their needs met more healthily.

Importantly, knowing about this cycle and the fact that the more times people go around it, the more they gather the tools and knowledge they need, gives hope that change – lasting change – is possible, even if a woman has tried unsuccessfully to leave the relationship in the past. She can see herself as progressing, instead of failing.

Using this model for therapeutic change as a point of orientation, it becomes possible to use the key points of human givens addiction therapy to enable a woman to move through – and exit from – this cycle successfully. I start with the idea of developing discrepancy: the discrepancy between where she will be in, say, five years, if she stays in the relationship as it is and where she would like to be. First, it is important to gather real evidence about the relationship as it stands. There are many questions to ask. What needs does it meet? Is there any concrete evidence that the abuser will change? Is the abuser seeking help? Or does his behaviour simply represent an oft-repeated pattern? If it does, and things continue in the same vein, how much worse might things be after another five years? What are and will be the physical/social/emotional consequences of this? How will it affect any children involved? Are there any practical difficulties standing in the way of leaving or staying away from the relationship, such as financial difficulties or fear of an escalation of the abuse? Are there practical ways of addressing these?

The positive alternative

Next, the focus needs to shift towards establishing a positive alternative to staying in the relationship. What would she be doing if she were not experiencing an abusive relationship? What possibilities are there? What could she look forward to or enjoy? How does she think she might feel – or her children might feel – if they were living a life unclouded by an abusive relationship?

Next, the focus needs to shift towards establishing a positive alternative to staying in the relationship. What would she be doing if she were not experiencing an abusive relationship? What possibilities are there? What could she look forward to or enjoy? How does she think she might feel – or her children might feel – if they were living a life unclouded by an abusive relationship?

As we know, it is far more powerful and beneficial for a person to imagine a positive change – actually doing something different – rather than simply focusing on ‘not doing’ the relationship anymore. So I encourage a woman to imagine either something simple and immediate, such as the freedom to let the children play happily and noisily in the garden, without her having to worry about whether that will annoy her partner, or choosing to wear whatever she wants when she goes out, or else something more long term, such as re-kindling an old interest or taking up a new hobby. Having established cognitively what the alternative to the relationship could be, it is then powerful to use guided imagery to accelerate the learning process and help the woman connect with it emotionally, as she envisages the more positive future she has created for herself.

A technique I often use when developing discrepancy in this way is to guide a client, when deeply relaxed, on an imaginary walk along a road until she comes to a fork marked by a blank signpost. In one direction (to the left) lies her life as it could be in five years time if she goes back to or stays with her abusive partner. In the other direction, to the right, lies a successful new life without that relationship in it. I encourage her to walk in turn down the two roads, engaging closely with each experience, using all her senses. Finally, having done this several times, she returns to the fork and notices that the signpost now has writing on it, naming where the different directions lead. I ask if she can make out the writing and, often, with no prompting, she identifies one direction as life and the other as death. Finally, she decides which direction she will follow. In my experience, this is always the ‘right’ road because, of course, once a client has relaxed deeply and her rational mind can truly engage with her situation, it would be nearly impossible for her to choose the other. Time can then be spent rehearsing and deepening the possibilities opened up by her choice.

The imagery of the abuse which would occur, had she taken the road of staying in the relationship, is then called into play to help keep her away from it. I remember asking Becky at one stage what she thought of when her Jim texted her, telling her he loved her and wanted her back. Did she call to mind the pleasurable times in the relationship? And when, even though she’d decided not to text back, she found she couldn’t resist the urge to do so, was it the thought of the hug, the words telling her that she was special, the flowers, that made her do so? Was she setting up the expectation that returning to the relationship would bring her pleasure and make her feel good? Her answer was yes.

Changing the expectation

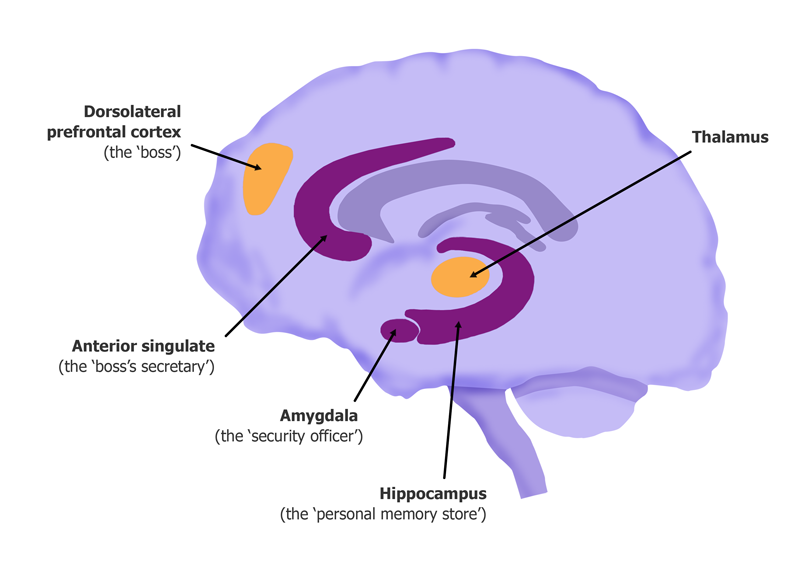

To help her to understand how she could find what she called ‘the willpower’ to stick to her decision not to return to Jim in the future, I used the idea of the brain as an office, originated by John Ratey4 and adapted by Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell,5 to explain what takes place in the brain when we are engaged in addictive behaviour. The boss is the thinker, who plans and forms expectations. The secretary keeps everything running smoothly and makes any routine decisions without bothering to involve the boss. But when she does need to consult him, she marks her message urgent by sprinkling it with dopamine (a cocaine-like brain chemical, which creates motivation and desire to take action). The filing cabinet is the place where all important personal emotional memories are stored. And the security guard is in charge of keeping the building safe. Incoming information is pattern matched against past experiences. If something is out of the ordinary and needs attention, he alerts the secretary, also sprinkling his message to her with dopamine to mark it urgent. I use this scenario with all the women I work with, to show why they might have returned to an abusive relationship in the past and may be tempted to do so again.

Becky and the secretary

As Becky has left Jim after their violent, two-year relationship, a message has been sent from the ‘boss’ to the rest of her brain, announcing that there will be no more relationship with Jim. During the daytime, Becky is keeping herself busy, looking after her daughter and sorting out the practicalities of a new life on her own. Because her focus is on her positive expectations for her new life and she is occupied in working towards this, any withdrawal symptoms from the relationship are very slight. In the evening, however, once her daughter is in bed and she is alone in an otherwise empty house, Becky begins to feel lonely. She calls to mind the pleasurable evenings she spent with Jim when they were courting and before the abuse began. At that moment a text comes through from Jim on her phone, telling her he loves her and that things will be different. The security officer, who receives incoming information first, is completely confused. On the one hand, there has been a clear order from the boss saying “no more relationship” – on the other, he can clearly see the loneliness and emotional distress that this is causing. He alerts the secretary.

The secretary realises that this is a complicated situation and so she goes in search of more information. She requests a file from the filing cabinet that will show her what the relationship with Jim has done for Becky in the past. It is at this stage that a series of images showing how much Becky has enjoyed Jim’s company on occasions, how painful it has been to try to live without him and how lovely it is to be sent flowers flash through Becky’s mind. The secretary is duly convinced that Jim is significant and necessary to Becky’s life, as the files confirm the expectation that returning to the relationship will bring pleasurable experiences. As in many offices, the secretary likes to feel that she is the one who is really in charge and so she drafts a letter granting permission for Jim’s text to be replied to. She then sprinkles it with as much dopamine as possible, to give it priority over everything else, and sends it to the boss to okay and sign. The boss takes one sniff of the dopamine and the urge to contact Jim becomes overwhelming. The secretary gets her way and the boss signs the letter. Becky texts Jim.4

Changing the files

So Becky needs to be able to ensure that the memory files which the secretary fetches are not of those brief pleasurable moments (false memories, distorted by the dopamine with which they are laced) but are realistic depictions of the violence, control and degradation that characterised the relationship. The files containing an expectation of pleasure need to be replaced by files containing an expectation of renewed distress, if she makes contact with Jim (Becky chose to use the image of being curled up on the ground in a fetal position, with her ex-partner spitting on her), while the expectation of pleasure transfers, instead, to the imagery of the new life Becky has clearly envisaged for herself. It is essential that she understands that she is responsible for ensuring that her ‘filing cabinet’ is kept in order, so that any information retrieved by the secretary will be up to date and that no positive files are left lurking at the bottom of the cabinet. Alongside this, it is important (as when striving to overcome any addictive behaviour) that Becky makes a plan for dealing with any danger times, when the withdrawal symptoms from the relationship – the pangs of loneliness, for example – could become overwhelming. This could include making arrangements to meet with or call friends and having other enjoyable activities planned – in short, using her own resources to fill her time healthily and focus attention away from the addictive behaviour.

Remaining angry is risky

It is fairly commonplace for therapists working with women who have left abusive relationships to allow or even encourage them to talk repeatedly (beyond the often essential and cathartic telling of their story and feeling heard and understood) about ‘the bad stuff’ that has happened to them. Revisiting the abuse and misery time and time again, without being introduced to any therapeutic tools to enable them to move forward, naturally stirs up huge amounts of emotional arousal and distress. For many women, it generates intense feelings of anger – or stokes any anger that is already, quite justifiably, present. In so far as emotions are the drivers that make us take action, anger can indeed be the emotional trigger for making a woman leave an unhealthy relationship. But when we draw on our understanding of addiction and how to overcome it successfully, it is clear that, once a woman has left the relationship, once the action has been taken, remaining angry or becoming increasingly angry simply puts her at added risk of returning to it.

Anger (just like that other strongly arousing emotion, love) forces us into black-and-white thinking and into relying on the more primitive part of our brain, which cannot think rationally and is prone to making rash decisions. When we are angry but can take no action we feel uncomfortable and naturally want to escape from those feelings. And just as an alcoholic might well reach for the bottle to try to wash away those unpleasant feelings, even if the anger is at him- or herself for wanting a drink, or an ex-smoker might, at that point, pick up a cigarette for the same reason, so a victim of domestic abuse might reach for the relationship. If the relationship was the only thing that had given her any fleeting sense of ‘high’, once other meaningful aspects of her life had been closed down by her partner, she might well crave it again when she feels impotent with anger and can’t see any other way to get rid of it. The fact that the relationship is the cause of the anger seems, at this point, to become almost lost and, in her mind at the time, the only way to dispel the unpleasant arousal is to go back to it and imagine that all will be different.

Closing the angry files

Helping a woman, once she has left an abusive relationship, to deal effectively with any anger that she is feeling so that she can think clearly and make good decisions is essential. If she remains angry when the need for action is past, she is at continual risk of being hijacked by her overwhelming emotions into returning to the relationship or getting involved in another, similar one. I have found the technique of closing angry files, adapted for a client’s particular circumstances, very useful in such cases, as a means of helping women to express their anger in a powerful but safe way and put it firmly in the past.6

GP Mona Mahfouz, who developed this technique to help clients whose unresolved and unexpressed anger was getting in their way, has described giving them a printed sheet, with instructions to carry out at home. The first paragraph of the sheet summarises very clearly what happens when anger stays unresolved, “If at any time in our lives, we have felt strong anger towards someone and were unable to express it, an ‘open angry file’ is created in our minds. This is done on purpose by our brains, to protect us from what the brain perceives as a ‘dangerous enemy’. Whenever we … think about this person (and there may be several of them), we will feel angry. And if we meet someone who just looks or acts like this person, we will also suddenly feel angry, even though we don’t make the connection and therefore don’t understand why! Such anger can cause problems as we suddenly explode or become irritable for seemingly trivial reasons or for no reason at all. Feeling angry so much of the time makes us feel unhappy, on edge and stressed.”6

I do not give a printed sheet to my clients but, as Dr Mahfouz instructs, I guide them, whilst deeply relaxed, to relive a time when they felt enormous anger against their former partner, perhaps when they felt most helpless against his abuse, and, in their imagination, to confront him fully with that anger, saying what they wish they could have said. I encourage them to see themselves as in full control and stress that they need feel no fear, as they are doing this in the safety of their own mind. They see themselves batting away any self-defence their partner offers and walking away the clear winner of the confrontation. Doing this dispels the anger because, as Dr Mahfouz puts it, the brain perceives ‘the enemy’ as now defeated and of no further threat. I stress clearly, however, that, although they will now be free of the anger that was hampering their ability to move forward and build their future, their capacity for anger, should they need it for self-preservation – if, for example, they were to encounter their ex-partner and feel threatened again – will remain intact.

I do not give a printed sheet to my clients but, as Dr Mahfouz instructs, I guide them, whilst deeply relaxed, to relive a time when they felt enormous anger against their former partner, perhaps when they felt most helpless against his abuse, and, in their imagination, to confront him fully with that anger, saying what they wish they could have said. I encourage them to see themselves as in full control and stress that they need feel no fear, as they are doing this in the safety of their own mind. They see themselves batting away any self-defence their partner offers and walking away the clear winner of the confrontation. Doing this dispels the anger because, as Dr Mahfouz puts it, the brain perceives ‘the enemy’ as now defeated and of no further threat. I stress clearly, however, that, although they will now be free of the anger that was hampering their ability to move forward and build their future, their capacity for anger, should they need it for self-preservation – if, for example, they were to encounter their ex-partner and feel threatened again – will remain intact.

Returning to needs

To fully break free of the cycle of addiction, it is essential, of course, to ensure that a client’s innate emotional needs are being met in new healthy ways (which is where I started with Becky) and this underpins anything else that human givens practitioners may do in therapy. Our needs are appetites; if we are starving and there is no other sustenance around, we will resort to eating mouldy bread and rancid butter. I remember once, at a workshop, the tutor asking us a question to help us put ourselves in the place of a frightened child engaging in self-defensive, destructive behaviour: “If you were in the middle of the Atlantic, hanging onto a lifebelt after a shipwreck, knowing that you would survive just a few hours in the cold, open ocean, would you leave it and start swimming, just in case there might be a life raft over the horizon?”7 The answer, of course, is no. Only if we could actually see the life raft would we let go of the little security we think we have, however fragile and false, and strike out towards it. Key to clients’ successfully leaving an unhealthy relationship behind is helping them to construct a life where their needs are met in healthy ways, where they have evidence that they are sleeping better, feeling calmer, have a sense of control, of status, of connection – and where they begin to experience the real emotional ‘high’ of getting their needs met in balance within the context of a genuinely healthy life.

As I have discovered through my work with Becky and other women in similar circumstances, when this understanding of the innate emotional needs is coupled with an understanding of how addiction hijacks the pleasure-circuitry of our brain, the outcomes for women seeking to leave and remain free of abusive relationships are all the more powerful and positive.

Ros Jeal has a private psychotherapy practice at The Beacon Clinic in Cornwall and also works for a national charity which provides support, shelter and counselling for women who have experienced domestic abuse. She is a member of The Grove Consultancy, with fellow human givens therapists John Halker and Nick Meredith, and is on the board of the Human Givens Institute.

This article first appeared in “Human Givens Journal” Volume 18 – No. 3: 2011

Back issues available – each issue of the HG Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more, with no advertising. If you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach, you can buy a back issue today, they’re available in PDF and print format.

References

- Griffin, J (2004). Great Expectations. Human Givens, 11, 1, 12–19.

- Survey of Domestic Violence Services (England) Findings (2004). Women’s Aid.

- DiClemente, C C and Prochaska, J O (1985). Processes and stages of self-change. In S Shiffman and T A Wills (eds) Coping and Substance Use. Academic Press.

- Ratey, J (2001). A User’s Guide to the Brain. Little, Brown and Company.

- Griffin, J and Tyrrell, I (2005). Freedom from Addiction: the secret behind successful addiction busting. Human Givens Publishing, East Sussex. In this book, the authors developed the idea of ‘the boss’ and ‘the boss’s secretary’ from John Ratey’s concept of ‘the chief executive officer’ and ‘the executive secretary’, to describe the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate structures of the brain.

- Mahfouz, M (2008). Closing angry files. Human Givens, 15, 4, 34–8.

- Every child does matter: how to transform the lives of challenging children and adolescents. A one-day workshop with Mike Beard. Mindfields College