A devastating death

Janine Hurley describes how the HGI Ethics Committee helped her cope, professionally and personally, when, tragically, a client killed herself.

I had just come back from a wonderful holiday when Jocelyn’s mother rang me and broke the terrible news that Jocelyn had jumped from a railway bridge and killed herself.

The shock was all the worse because Jocelyn had been doing so well in our sessions. As our therapy had progressed, I had come to know her as a vivacious, attractive, talented young woman, a far cry from the withdrawn, agitated girl whom I had first met 10 weeks previously.

Jocelyn was in her second year at university, studying sociology. It was spring and she was extremely worried about her end-of-year exams and a long essay she was struggling with. She had been having what was clearly an intense and toxic relationship with a fellow student, who was highly possessive and jealous, extremely critical, and disparaging of her as a person. Because she was studying so hard and worrying so much, she appeared mentally and physically exhausted when I first met her. By that time the boyfriend had broken off their relationship, which upset her enormously, as she had convinced herself that she was totally in love with him and could not live without him. She was hardly sleeping or eating and, on a couple of occasions, she had misused tranquillisers and alcohol to a degree that she had ended up in the accident and emergency department.

Jocelyn told me that she felt uncertain of her sanity at times, reporting a couple of what appeared to have been psychotic episodes. She said she suffered very low self-esteem, poor concentration and racing thoughts, felt overwhelmed most of the time and was unable to complete the tasks she needed to do. Her GP knew about her state and had referred her to the mental health service, which meant she was on a long waiting list for cognitive-behavioural therapy.

I use the CORE psychometric system for rating clients’ distress from a variety of symptoms and measuring changes each session1, and this revealed that, over the previous week, she had contemplated self-harm and was severely depressed. I discussed with her whether she still had any suicidal intentions or plans and she replied that, although she felt very sad, she no longer had any intentions of taking her own life. We agreed a care plan, which involved teaching Jocelyn skills to manage her stress through breathing techniques and relaxation exercises (I gave her a CD with a relaxation induction); teaching her some missing life skills, such as thought control, managing setbacks, and communication and assertiveness techniques; carrying out an emotional needs audit to identify important needs not met and work towards finding ways to meet them; and giving her the knowledge to help her to live her life in a healthier way. She left our first session feeling motivated and hopeful about the future.

When we met again two weeks later, Jocelyn’s CORE scores showed that she still had low mood but was no longer severely depressed and was not thinking about harming herself. She said that she had been using the CD and breathing techniques, that her sleep had improved, and that she had been paying better attention to her diet and had taken a break from drinking alcohol. She was still very distressed and angry about the break-up of her relationship and we worked on this, challenging her negative thinking styles. Again, she seemed positive and optimistic when she left the session.

By two weeks later, at our third session, the vivacious Jocelyn had surfaced. Her CORE scores showed a significant positive shift in mood and she was no longer at risk. She confirmed the change, saying that she felt much better, was far less anxious, had kept off the alcohol and had noticed the benefits of this for her physical health. Her sleep was still not good, however; she was in a pattern of getting up at 5am to begin on her essays and waking even earlier to worry about them. As I couldn’t shift her from this pattern, we agreed on a daily routine that included proper food and rest breaks. She mentioned that she was back in touch with her boyfriend but was being careful not to get sucked back under his spell.

At what was to prove our final meeting, Jocelyn’s CORE scores attested to her continuing improved mood and emotional wellbeing. However, she had ticked the ‘occasionally’ box for the statement, “I have made plans to end my life”. When we discussed this, she insisted she had no real intention or plan to hurt herself and it was just a fleeting thought she might have when she was over-tired and particularly worried about all the work she still had to do. She did say, however, that she had resumed her relationship with her boyfriend and that it had quickly become intense again, distracting her somewhat from her academic work. But she insisted that she was still seeing other friends and engaging in a variety of interests and that she was continuing to practise the relaxation techniques. We worked on how she could maximise and maintain her mental wellbeing.

At what was to prove our final meeting, Jocelyn’s CORE scores attested to her continuing improved mood and emotional wellbeing. However, she had ticked the ‘occasionally’ box for the statement, “I have made plans to end my life”. When we discussed this, she insisted she had no real intention or plan to hurt herself and it was just a fleeting thought she might have when she was over-tired and particularly worried about all the work she still had to do. She did say, however, that she had resumed her relationship with her boyfriend and that it had quickly become intense again, distracting her somewhat from her academic work. But she insisted that she was still seeing other friends and engaging in a variety of interests and that she was continuing to practise the relaxation techniques. We worked on how she could maximise and maintain her mental wellbeing.

A few days later, she texted me, panicked about not being able to concentrate on her studies. I replied with suggestions for a routine and the next day she texted that the routine was helping and that she was feeling and working better. A week later I posted her a CD of a sleep induction session and texted her to say so. She replied that, although still stressed about her essay, she was staying calm, keeping to her routines and was sleeping better. She mentioned that she was seeing her GP the next day. We agreed to have another appointment two weeks after that, on my return from holiday. Alas, by then she had died.

Apparently, as her mother told me later, in the few days before her untimely death her stress levels had soared because she did not think she was getting the support she needed from her tutor to help her with a difficult piece of work, could hardly sleep at all and was again going through a very bad patch with her boyfriend. Jocelyn had rung her mother a number of times to say how stressed she was feeling but her mother did not realise the seriousness of the situation, as it was the pattern for Jocelyn to seek assurance whenever she was stressed and then to become calmer. To make matters worse for Jocelyn, her two flatmates had finished their exams and gone home, so she was alone, all her support structures suddenly stripped away from her at once.

A whole gamut of emotions

After Jocelyn’s death, when the police checked her phone for calls that she had made or received over her final days, it was revealed that her boyfriend had told her that he wished she were dead. (He was unable to be contacted afterwards.)

I experienced a whole gamut of emotions at this terrible time; I was distraught that such a beautiful, gifted young woman had needlessly died, racked with anxiety about whether I could have done anything differently to prevent her death and, after the police contacted me to ask for a statement about the work I had done with Jocelyn, worried also about any professional repercussions. I was contacted at least twice a week for some months by Jocelyn’s mother, as she and Jocelyn’s father tried to piece together and make sense of their daughter’s last few days and, while I was only too glad to provide emotional support and also any information I could find that might help them understand Jocelyn’s actions and state of mind, this was additionally emotionally demanding. I was very grateful that my human givens supervisor was available to help me overcome the trauma and to talk over my feelings and fears, one of which was that the focus of my therapy might shift, with the analysis of risk becoming overwhelming and unhelpful, reflecting my own insecurities, rather than the focus being on the needs of the client.

As requested, I wrote out a statement to give to the police: this included the dates of all contact with Jocelyn, including texts; all her psychometric scores; my initial assessment of her case and her level of vulnerability; a summary of what we addressed in each session; the care plan we had established and my own conclusions. Then it occurred to me to ring the Human Givens College and ask if there was a policy I needed to follow for all this. My request was directed to the HGI Ethics Committee, one of whose members, Ian Thomson, contacted me immediately and, to my lasting gratitude, expertly guided me through every step of what was to follow.

Preparations

Ian asked me to send him the statement I had prepared and sent it around to the other members of the committee, who all read and commented on it. It helped me enormously that they were extremely positive about the work I had done and said that, in their view, therapeutically I could not have done more. Ian deftly improved the structure and wording of the statement, to make it more of an objective report than a personal account.

Importantly, he suggested that I avoid terminology that would have meaning mainly for human givens practitioners, such as trance and 7/11 breathing, and instead use terms such as structured relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing. Ian advised me to inform my professional insurers about what was happening. They in turn offered advice and kept a copy of my statement on file. Ian also located and sent me material about the structure of the teenage brain, which could account for emotional outbursts and reckless risk-taking behaviour. I was able to send this to Jocelyn’s mother, which gave her some understanding and comfort.

After my statement was submitted to the police, Jocelyn’s mother told me that the coroner who would be presiding over the inquest was concerned whether the mental health services that should have met Jocelyn’s needs had been seriously flawed. I had hardly digested this when I received a letter from the coroner summoning me to attend the inquest myself – giving me just one week’s notice and informing me that I would be fined £4,000 if I didn’t attend. The day before the inquest, I was told that the coroner was questioning whether the human givens approach was a bone fide therapy, as it fell outside NHS provision. I felt extremely threatened and again called the Ethics Committee for advice. Once more, Ian gave his time to talk to me on the phone and either emailed or directed me to supportive backup material. And I was immensely grateful to Bill Andrews, champion of outcomes measures for the Human Givens Institute, who, the night before the inquest, emailed me information from a very poor link in a hotel and talked me through what I needed to know about CORE and the NICE guidelines. He was due to give a lecture the following day.

I took with me to court, to add to the statement which the police had already passed to the coroner, a diagram of the human brain, the published paper showing the positive outcomes from human givens therapy in a primary care setting2, plus a brief description of the human givens approach I had prepared, which set it in the context of neuroscientific discoveries about the brain and its empirically grounded clinical interventions. I also included information about the structural brain changes at adolescence, which, according to some experts, may explain why first episodes of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (known to contribute to the rate of teenage suicide) commonly occur at this age. While hormones ‘rage’ at this time, affecting emotions and behaviour, the prefrontal cortex, which normally supplies the judgement and applies the brakes, is shrinking, as neural connections made in pre-teenage years are pruned. So, at this crucial period, teenagers do not always have full access to the cognitive abilities that guide more mature behaviour 3,4.

I was quite daunted at the prospect of being questioned in court by the coroner but, unfortunately, no one from the Ethics Committee was able at such short notice to attend to give me support, and considerable travel and time would have been involved. I decided, in the end, to be accompanied by my grown-up daughter. The hearing was set for two hours and the setting was similar to an ordinary courtroom, with us all having to swear on the Bible before giving our evidence.

The coroner was markedly tenacious in his questioning and criticised both the GP and the local mental health service, represented by a manager, for failing to respond adequately to Jocelyn’s needs. When it was my turn to take the stand, the coroner didn’t question the human givens approach, perhaps because Jocelyn’s mother had said that she thought it was the most effective help that Jocelyn had received. Instead, he asked if I thought the death was unexpected and whether anything could have been done to prevent it. I was able to produce and explain the psychometric charts, show that her risk of self-harm had fallen almost to zero and that she had quite clearly responded to therapy. When he countered that by demanding how I could be sure that she didn’t just pay lip service to the therapy, I showed the Session Rating Scale (SRS) forms5, which Jocelyn had completed at the end of each session; this asks clients to scale how far they felt that they had been heard and understood, had talked about and worked on what was important to them, felt the therapist’s approach was a good fit for them and whether anything was ‘missing’ in that day’s session. Jocelyn’s scores were consistently very positive. I could also affirm that she engaged keenly with the therapy, would report whatever she was doing differently as a result and that she had calmed down.

If the coroner had given an open verdict, this would have implied that her death could possibly have been prevented. Instead, his verdict was that Jocelyn took her own life, which was a relief to the family and to me, as it helped us to cope just a little better with what had happened. As her mother wrote in an email to me afterwards, “she rang me to say goodbye and not to be talked out of it”. In the same email, she told me that Jocelyn had clearly liked coming to therapy and was happy and confident to do what I had suggested and was making progress.

As the months pass, the impact of this devastating experience on my own life is subsiding, even though this will never, alas, be the case for Jocelyn’s family. I want very much to say how much I valued and appreciated the support given to me by the members of the HGI Ethics Committee, particularly Ian Thomson. I had no idea, before this tragic event, that such a service existed. Even though, as for many human givens practitioners, I have often felt that I am working in isolation, we are not really in isolation at all and all the support one could want is there when we need it. This is particularly remarkable because, as we are only a small organisation, the members of this committee give their time and expertise for free.

I do think, however, that it would be enormously helpful to have support and advice at an inquest from a fellow professional and would like to suggest that anyone willing to support a local colleague in this eventuality contacts the college to have their name put on a register. I shall be the first to add my name to any such list, as this has been one of the most difficult experiences I have had to face in my life, both personally and professionally. On the plus side, the human givens approach was well represented throughout and my trust in its efficacy is further strengthened by how well it stood up to scrutiny.

All identifying details have been changed.

Points to remember

Janine’s case highlights how important it is to take good notes of therapy sessions and to use outcomes measures, which show symptom change from session to session, along with clients’ own evaluation of their therapy. We would suggest that anyone in a similar situation should:

- produce a succinct summary of the human givens approach, backed up by references supporting the approach, and mention that it is used by a number of GPs, psychologists and psychiatrists

- refer to specific aspects of human givens treatment using the terminology of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) – for instance, diaphragmatic breathing or controlled breathing (7/11); structured relaxation (inducing trance); deep relaxation (guided imagery) cognitive restructuring (challenging and changing unhelpful thoughts); cognitive reframing (reframing) and imaginal exposure (rewind technique)

- have to hand details of up-to-date research evidence of human givens effectiveness (eg the paper by Andrews et al2 and Yates and Atkinson6)

- be able to show psychometric scores for all the client’s sessions

- be able to produce good notes of sessions

- make the indemnity insurer aware of the situation, providing them with a copy of any relevant written statement and seeking their advice where necessary.

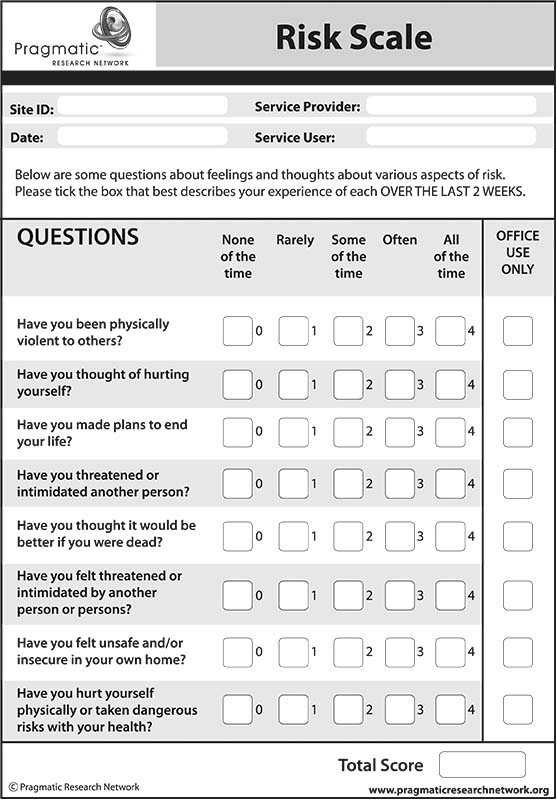

Whilst, as illustrated by this case, it is not always possible to affect the outcome, it is important that therapists carry out an assessment of risk in relation to suicide/self-harm with each client they see. Question 6 of the CORE 10 client questionnaire* covers a key indicator of risk (“I made plans to end my life”) and the ‘Risk Scale’* (see above) is designed to facilitate a more detailed risk assessment. In addition, therapists should be prepared to discuss any risk-related matters in an open and straightforward way with clients.

It is also important to ensure that clients understand the limits of confidentiality, ie that all the information they provide will remain confidential except where the therapist believes there may be risk of harm to the client or others, or where there is content of a criminal nature. A service user agreement* is available that covers this.

The HGI Ethics Committee is happy to help in every way possible but cannot offer legal advice.

Ian Thomson – HGI Ethics Committee

Ian Thomson – HGI Ethics Committee

* (downloadable from www.pragmaticresearchnetwork.org)

JANINE HURLEY is a human givens therapist. She has previously worked as a children’s nurse, having trained at the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Sick Children. She also trained as a health visitor and, in the past year, has taken early retirement from a long career in this field, choosing to concentrate on her work as a triage nurse in the NHS and as a counsellor in private practice.

This article first appeared in the Human Givens Journal – Vol 18, No. 4: 2011

Back issues available – each issue of the HG Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more, with no advertising. If you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach, you can buy a back issue today, they’re available in PDF and print format.

References

- CORE Information Management Systems (2002). National Comparative Performance Indicators and Service Descriptors: a benchmarking guide for services providing brief psychological therapy services in the UK. CORE IMS, Rugby.

- Andrews, W, Twigg, E, Minami, T and Johnson, G (2011). Piloting a practice research network: a 12-month evaluation of the human givens approach in primary care at a general medical practice. Psychology and Psychotherapy: theory, research and practice, doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.2010.02004.x

- Herrman, J W (2005). The teen brain as a work in progress: implications for pediatric nurses. Pediatric Nursing, 31, 2, 144–8.

- Wallis, C (2004). What makes teens tick? Time, 163, 19, 56–65.

- Duncan, B et al (2003). The session rating scale: psychometric properties of a ‘working alliance’ scale. Journal of Brief Therapy, 3, 1, 3–12.

- Yates, Y and Atkinson, C (2011). Using human givens therapy to support the wellbeing of adolescents: a case example. Pastoral Care in Education, 29, 1, 35–50.